The Future of Baby-Making

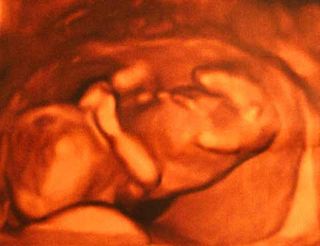

The second set of octuplets ever born in the United States arrived this week, raising questions about the future of baby-making and fertility medicine, a field that has made dramatic advances since the first test-tube baby was born three decades ago.

Hospital officials reportedly refuse to reveal if the new octuplets' mother, who gave birth early Monday in California with the assistance of a medical team of 46 people, used fertility drugs, but Dr. Richard Paulson, director of the fertility program at the University of Southern California, told the Associated Press that it is likely.

Fertility experts see the birth of octuplets as a serious medical complication, not a triumph of reproductive technology.

"That's not what we consider a success," said Dr. Jamie Grifo, program director of the NYU Fertility Center and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the NYU School of Medicine, referring to the new octuplets. "We try to avoid twins, let alone triplets because of the risks. A single birth is risky. Twins are more risky. Triplets — it is exponentially more risky."

Infertility affects about 20 percent of all U.S. women at some point in their reproductive lives, Grifo said, and that figure is likely to rise as more and more women have children later in life. Reproductive efficiency at age 30 is twice that of women at age 40, he said. Men do not experience a big change in fertility with age, he said.

Fertility treatments could be a factor that will result in declining fecundity (potential for fertility, such as regular menstrual cycles) across the generations, according to a 2008 editorial by Jens Peter Ellekilde Bonde at Aarhus University Hospital Denmark and Jorn Olsen at the University of California, Los Angeles, published in the journal BMJ.

Assisted conception makes it so "subfertile couples may have as many children as fertile couples, so that genetic factors linked to infertility will become more prevalent in the generations to come," the authors wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fewer multiple births in future One of the breakthroughs in fertility medicine in years to come will be fewer multiple births, Grifo said, and the decline is already under way. "I can't remember the last time we saw more than triplets, and now we have our triplets down to a very low percentage of deliveries," he told LiveScience. About a quarter of all infertility problems in women are related to ovulation problems, so one of the most common treatment approaches is medicines such as Clomid (clomiphene citrate) which can induce the ovulation of follicles — clumps of cells that include the egg or ovum. The challenge is controlling the number of follicles induced, which can lead to multiple births, but proper dosing can help, Grifo said. Clomid is relatively inexpensive compared to other fertility treatments, such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF or "test tube babies"), so for that reason and others, the typical sequence that many patients with fertility problems go through is to start treatment with Clomid. If that fails, the sequence tends to be to then try an injectible ovulation inducer, then IVF if the injections fail, and then an egg donor, with corrective surgery as a possibility along the way for some patients. Clomid treatment, in Grifo's practice and research, results in a doubling of the natural pregnancy rate, he said. The twin percent rate is naturally 2 percent and goes up to 8 percent with Clomid treatment, and the triplet rate with Clomid is 1 in 1,000, "so for us we found it very useful," he said. "Our experience with injectibles is a 10 to 20 percent pregnancy rate per cycle. You can do it safely; you just have to be more careful," Grifo said. Advances with 'test-tube babies' The most effective treatment for infertility is IVF, Grifo said, giving the following success rates (delivery): * for those under 35 years old, more than 50 percent; * up to age 38, 34 percent; * age 40, 29 percent; * age 43, 15 percent, * age 44, 6 percent. Grifo's team also is involved in "blastocyst culturing" prior to IVF, which involves culturing embryos for up to five days and then implanting only the best one or more embryos. "We're at the point where we are doing single embryo transfers," Grifo said, adding that his team will soon publish research describing this process and its successes — very high pregnancy rates in a select group of patients, resulting in no triplets and very few twins. Questions about Clomid A study last year in the journal BMJ Online found that medical interventions for infertility did not improve fertility. The researchers compared the effectiveness of oral clomiphene citrate, intrauterine insemination (IUI, also known as artificial insemination, involves injecting sperm into the uterus) and just trying for a natural pregnancy with no medical assistance. The subjects were women who had experienced unexplained fertility for more than two years. Women who had no interventions had a live birth rate of 17 percent, while the clomifene citrate group had a birth rate of 14 percent and the group having IUI had a birth rate of 23 percent. Grifo called that an "awful study" and said he could not believe it was published. The treatment group excluded patients who responded optimally to clomiphene citrate to avoid multiple births, he said, so the group only included poorly responding patients who already had a low pregnancy rate.

Designer babies concerns

Advances in genetics are opening the door to such baby-making approaches as reprogenetics, which could theoretically make it possible for parents to control the genetic make-up of their children before they are born, via screening or even engineering of genes.

Such scenarios raise the specter of designer babies in the minds of some, as well as potential discrimination against people deemed to be genetically inferior, as envisioned in the 1997 feature film "Gattaca."

In reality, people are highly interested in additional genetic testing of fetuses for life-altering and threatening medical conditions such as mental retardation, blindness, deafness, cancer, heart disease, dwarfism and shortened lifespan, according to a new study by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center.

Consumers are less interested in prenatal genetic testing for tall height, athleticism and intelligence, said researcher Feighanne Hathaway. The study is detailed in the Jan. 22 online early edition of the Journal of Genetic Counseling.

"Our research has discovered that although the media portrays a desire for 'designer babies,' this does not appear to be true among consumers of genetic testing services," Hathaway said in a prepared statement.

Over-medicalized pregnancy? Some critics of fertility medicine state that it "over-medicalizes" pregnancy and delivery, which should remain more natural. Grifo objected vociferously to that assertion, calling some of these comments "incredibly caustic." The option for infertile women and men is to deny them treatment so they don't have a medicalized pregnancy, Grifo said, adding: "Ask a patient what they would rather have — no pregnancy or a medicalized pregnancy. They want to have a baby and they are willing to put up with inconveniences and some of the risks." "My patients are as depressed as cancer patients," he said. "Why would that be? When you tell someone they have cancer, you change their life. When you tell someone they can't have a baby, you change their life, and it's not a straightforward, cosmetic kind of thing. This is a big-ticket item."

- All About Babies

- The History and Future of Birth Control

- Pregnancy: News and Information

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Most Popular