Scientists Zero In on Earth's Original Animal

Sea sponges have been thought by some scientists to be the most primitive living animals, the closest living things to approximate Earth's original animal, down at the base of the tree of life for the animal kingdom.

But the squishy things are now being pushed aside by a group of amoeba-shaped creatures called Placozoans, according to a new analysis which shows the fairly simple but still multi-cellular animals are closer to the base of the tree, researchers say.

A weirder result follows from the fact that the analysis finds that corals, jellyfish, sponges, comb jellies and Placozoans (aka the "lower" animals) evolved in parallel to "higher" animals including flatworms, insects, mollusks and chordates (which includes all animals with backbones, ranging from frogs to apes and humans).

Nervous systems are found in both groups (among the lower animals, jellyfish have nervous systems), so the new arrangement means that these systems must have evolved twice in the history of animal evolution, said Rob DeSalle, a biologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York who did the analysis along with Sergios-Orestis Kolokotronis, also at the museum.

DeSalle said the finding is unsurprising to him. "Things in organisms that look alike a lot of times aren't really derived from a common ancestor," he said. "The nervous system of cnidarians [a lower animal group that includes corals, jellyfish and hydras], and Bilateria [the higher animals group that includes humans] are constructed with the same molecules and often times using the same genes. But it is possible that the cnidarians' nervous system really is not the same nervous system found in Bilaterians." Many lower animals other than jellyfish lack nervous systems, DeSalle said, but they could have the rudiments of a nervous system and we just haven't seen them. "Placozoans and sponges both have genes for nervous systems in their genomes," he said. "They just don't do it. They don't make it."

More about Placozoans

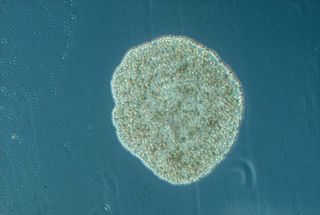

Most of us have little experience with Placozoans. They form into sheets on rocks and corals in temperate seas and "are really cool to watch and they move by undulating. There are no muscles," DeSalle said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Placozoans were discovered about 100 years ago growing on side of a laboratory aquarium in Germany, DeSalle said, and have subsequently been discovered living in the wild. A number of other recent studies, using cluster computers to crunch big matrices of data to arrive at the best explanation for animal evolution, have tackled the question of the details of the ancestry of all animals and also found Placozoans at the base of the animal tree of life. But DeSalle said the new tree is strong because it included some key species that other analyses omitted, as well as considering a large number of traits and finding very strong support. Bernd Schierwater of the Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover in Germany designed the study and contributed data and analysis assistance for the study which was published in the latest issue of the journal PLoS Biology. The research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Lower Saxony Graduate Program and the Human Frontier Science Program. Evolutionary twists The new tree also underscores the fact that evolution does not proceed along a straight line, counter to many cartoons. And it's pretty common to find things evolving more than once, DeSalle said. "You see that in other systems and kinds of anatomy — dorsal-ventral polarity in animals, which means having a stomach and back, has evolved twice. It's different in invertebrates and vertebrates. Even if you flip the things upside down, in other words, they are not the same," he said. And the eye is another example, he said. "They are incredibly complex things, but they have evolved many times," he said. The famous biologist Ernst Mayr once wrote a paper stating that the eye had evolved 25 different times in nature, so "it's not that far-fetched to think that the nervous system would have evolved twice," DeSalle said.

- Evolution: Information and News

- 10 Species You Can Kiss Good-bye

- Video – Life Rocks the Earth: Biologic and Mineral Evolution

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.