Gruesome Images Reveal Python Digesting a Rat

Gruesome 3-D images of the insides of snakes, alligators and tarantulas have been captured with a new high-tech procedure.

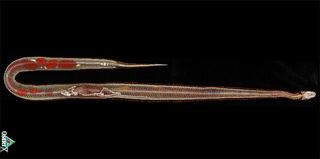

The digital images show for the first time the complete digestion cycle of a Burmese python, including how the animal adapts its internal organs in preparation for a big meal and during digestion until the snack has vanished. [Gallery of Animal Guts in Action]

The results are being presented Wednesday at the annual meeting of the Society for Experimental Biology in Prague.

"Pythons are renowned for their ability to fast for many months and ingest very large meals," said study researcher Kasper Hansen, of Aarhus University in Denmark.

Hansen and colleagues wanted to see how extreme adaptations of the internal organs allow the snake to accommodate this "feast and famine" lifestyle.

They used a combination of computer tomography (CT), which is suited to hard tissue (bones, teeth and shell) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), more suitable for soft tissue, to visualize the entire internal organ structures and vascular systems of their animal subjects.

Fasting Burmese pythons (Python molurus) were scanned before and at two, 16, 24, 40, 48, 72 and 132 hours after ingestion of one rat. The succession of images revealed a gradual disappearance of the body of the rat, accompanied by an overall expansion of the snake's intestine, shrinking of the gallbladder, and a 25-percent increase in heart volume.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By choosing the right settings for contrast and light intensity during the scanning process, the scientists were able to highlight specific organs and make them appear in different colors.

In addition, some species such as turtles, swamp eels and bearded dragons were also injected with contrasting agents, which allowed the scientists to peer into their blood vessels. Other images showed frog lungs and alligator anatomy.

The non-invasive CT and MRI scans could let scientists look at animal anatomy without the need for other invasive methods such as dissections.

"Because of the changes induced by dissection, ordinary illustrations tend to be a bit subjective and sometimes misleading," Hansen said. "For example, after opening the dense bone of a turtle shell, the lungs will collapse due to a change in interthoracic pressure."

- Gallery of Animal Guts in Action

- 7 Shocking Snake Stories

- Top 10 Deadliest Animals