First-Ever Image of a Terrestrial Gamma-Ray Burst Shows Light Exploding Out of a Thundercloud in Asia

Gamma-rays are the highest-energy form of light in the universe. They burst out of distant galaxies following some of space's most extreme events — massive suns exploding, hyper-dense neutron stars crashing into one another, black holes gobbling up worlds of matter, etc. — and, when they do, their glow briefly outshines every other light in the sky. (That is, if you can catch them with a gamma-ray telescope.)

Sometimes, however, gamma-ray bursts pop up where scientists don't expect to see them — like in Earth's atmosphere, for example. These so-called terrestrial gamma-ray flashes are produced by near-light-speed electron interactions inside giant thunderclouds, but scientists aren't exactly sure how they happen. Lasting only about 1 millisecond long, the mysterious bursts of energy are difficult to pinpoint and study in detail.

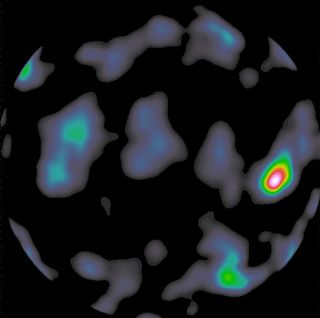

Now, after one year of observing Earth from space, researchers have created the first-ever image of a terrestrial gamma-ray flash, which erupted out of a thunderstorm over the island of Borneo, in Southeast Asia, on June 18, 2018. As seen above, the colorful cigarette burn of red-white light on the far right of the image shows the burst's most energetic region.

Astronomers observed the storm from a special observatory aboard the International Space Station, which launched in April 2018 with the purpose of monitoring the entire visible face of Earth for terrestrial gamma-ray activity. Hopefully, this is just the first of many such images. After one year of operations, the observatory has captured more than 200 terrestrial gamma-ray flashes, and was able to pinpoint the exact geographic location of about 30 of them, according to a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

When researchers know the precise location of a given gamma-ray burst, according to the statement, they can compare their data with other satellites and even local weather stations to paint a better picture of the forces that coalesce to create the fleeting flash of energy.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 15 Amazing Images of Stars

- 9 Strange Excuses for Why We Haven't Met Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.

Most Popular