King Tut's Sisters Took the Throne Before He Did, Controversial Claim Says

Archaeologists have known that a "mystery female pharaoh" ruled ancient Egypt before the renowned King Tutankhamun ascended the throne. Though they knew the royal name of this female king — Neferneferuaten Ankhkheperure — her true identity has remained elusive; however, Tut's famed tomb was originally meant for her.

Now, a researcher says the mystery woman might be none other than King Tut's two older sisters, according to the investigator's new, and controversial, research.

It's possible that after King Tut's dad, King Akhenaten, died, his youngest surviving daughter, Neferneferuaten, began ruling Egypt at age 12, likely at first disguised as a male. During this time, Neferneferuaten's older sister Meritaten served as her great royal spouse.

But Meritaten didn't keep that "great royal spouse" title for long. "It looks like after one year, Meritaten had herself crowned as pharaoh, as well," said researcher Valérie Angenot, professor of art history and specialist in visual semiotics at the University of Quebec in Montreal. "They actually ruled as two queen pharaohs, instead of this more traditional view of one pharaoh and one queen." [In Photos: The Life and Death of King Tut]

However, Angenot's idea about the "two queen pharaohs" is controversial among Egyptologists, many of whom think that the mystery queen is none other than Nefertiti, the principal wife of King Akhenaten and stepmother to King Tut.

Angenot presented her research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, at the annual meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt, held April 12-14 in Alexandria, Virginia.

King Tut's complicated family

King Tut (1341-1323 B.C.) has fascinated the public ever since British archaeologist Howard Carter famously uncovered Tut's tomb in 1922. But Tut's family tree is a complicated web; his father, the pharaoh Akhenaten, focused ancient Egypt's religious worship on one deity, Aten, the sun disk.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Plague hit Egypt during Akhenaten's approximately 17-year reign (1353 to 1335 B.C.). Even three of Akhenaten's daughters died during that time, possibly from the plague, Angenot said. "I believe that because of all these deaths, he kind of tried to prepare his succession," Angenot told Live Science. "He tried to prepare his four surviving children to be likely to rule at some point if the others died."

So, Akhenaten married his eldest daughter, Meritaten. Then, he had the next eldest daughter, Ankhesenpaaten, marry Tut so that when Tut became king, she would be queen (it was common for Egyptian royalty to marry within the family).

"Then, there was the little one, Neferneferuaten," Angenot said. "When everyone was dying, she was only 7. She couldn't be a great royal spouse, because she couldn't have babies and she could not carry on the bloodline. So, I think this is when he decided to make her a king instead of making her a queen. He had her crowned pharaoh."

If this theory is true, then the "mystery female pharaoh" who ruled immediately after Akhenaten's death, when Tut was too young to take the throne, was the youngest daughter: Neferneferuaten Tasherit.

Mystery queen

Egyptologists have known for at least 50 years that a mystery queen ruled following Akhenaten's death. A close examination of Tut's tomb showed that it was originally made for a woman; for instance, the funerary equipment still has traces of a female name. Many Egyptologists think that this mysterious woman was Nefertiti, who would have undergone a name change in her transition to pharaoh. Others think that the female pharaoh was Meritaten, who, after all, had married her father. But Angenot said it makes more sense that this mysterious Neferneferuaten is the youngest daughter, whose birth name was just that: Neferneferuaten. [Image Gallery: Amazing Egyptian Discoveries]

And it's not just a hunch. Royal names usually included birth names. "This is why I always suspected that neither Nefertiti nor Meritaten could be the king or that queen, because they don't have [Neferneferuaten] in their birth name," Angenot said.

"The only candidate who had this name as a birth name was the princess Neferneferuaten," Angenot noted. "The problem was that she was the youngest surviving daughter, so everybody thought she could not have had precedence over her siblings to sit on the throne."

But Angenot thought otherwise. In addition, she found evidence in Egyptian art that this mysterious female pharaoh was the princess Neferneferuaten. Angenot, an art historian, noticed that several sculptures of anonymous royal heads, which were previously thought to depict Akhenaten or Nefertiti, are actually of the young princess.

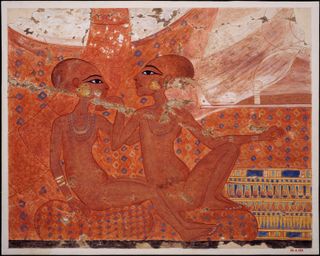

Moreover, a semiotic analysis (a deep dive into signs and symbols) of Egyptian body language revealed that a certain gesture — a caressing of the chin — is seen in paintings of Akhenaten and Nefertiti's daughters. This gesture is also seen in an unfinished stele (a carved stone slab) of two royals. This stele also bears royal iconography describing pharaohs, suggesting that once Neferneferuaten began ruling, her elder sister Meritaten joined her.

The king who ruled after Tut likely didn't approve of this co-female rule and so probably destroyed traces of the sisters' reign. "That's why we have such little information," Angenot said, "because everything was destroyed after their deaths."

Neferneferuaten and Meritaten would have shared the same coronation name, Angenot noted. Plus, a "female pharaoh" was not without precedent, as Egypt had already been ruled by Hatshepsut and Sobekneferu.

Another strike against Nefertiti being the mysterious female pharaoh, Angenot said, is that she wasn't part of the royal bloodline (that is, a daughter or sister, as other female pharaohs were), but simply the king's wife.

What's next?

Angenot described her research in a 20-minute talk at the conference, and she is now detailing it in a paper that she will submit to a scientific journal. Many Egyptologists are eagerly awaiting the paper's publication so they can get more details about this unusual theory.

"She made a good case, I thought, for the visual similarity of certain statues all belonging to one princess whose name we don't know," said Stephen Harvey, an Egyptologist and director of the Ahmose and Tetisheri Project excavation in Egypt, who attended Angenot's talk at the conference. "I'm looking forward to seeing how she develops the argument, in particular, for the idea of two women ruling simultaneously, because that is unheard of in 3,000 years of Egyptian civilization."

Others dismissed the idea. "[It's] completely incredible, as in not believable," said Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, who also saw the talk.

It's interesting that the "hand caressing the chin" gesture is associated with princesses from the 18th dynasty, but it's challenging to say that this gesture on the stele is evidence that two female pharaohs ruled Egypt, said Dodson. He is currently writing a book arguing that Nefertiti is likely the mysterious female pharaoh. [Photos: Ancient Egyptian General's Tomb Discovered in Saqqara]

Moreover, the unfinished stele has space for three royal cartouches (a long oval on which royal names were inscribed). This setting would typically fit the name of a king, who had two cartouches, and a queen, who had one cartouche. Dodson said that Angenot told him that because the two princesses likely shared a coronation name, the three cartouches would have been "Neferneferuaten Ankhkheperure Meritaten." But "there is no parallel to anything like this happening in Egypt before or afterwards," Dodson said.

In addition, Neferneferuaten "was part of Nefertiti's name from very early on" in her marriage to Akhenaten, Dodson said, so it wouldn't be a big leap if she started using that name as pharaoh after her husband's death.

Angenot's idea will be easier to assess once the study comes out, Harvey told Live Science. "I really want to hear the details of that," he said. "I want to give it a fair hearing."

- Peaceful Funerary Garden Honored Egypt's Dead (Photos)

- Photos: Mummies Discovered in Tombs in Ancient Egyptian City

- Purrfect Photos: Cat Mummies and Wooden Cat Statues Discovered at Ancient Egyptian Burial Complex

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.