Found: First Tibetan Evidence of Neanderthal Cousins, the Denisovans

For the first time, scientists have found fossils from an extinct ancient human lineage known as the Denisovans outside of Siberia.

Denisovans were an extinct group of hominins that were close relatives of Neanderthals. They are known primarily from a handful of fossil fragments found at Denisova Cave in Siberia, and from genetic clues that linger in the DNA of people across Asia.

But new fossil evidence reveals that these ancient human relatives also inhabited the Tibetan Plateau, the tallest and widest plateau on Earth, known as "the Roof of the World."

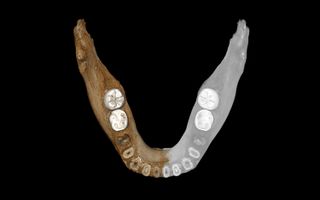

Protein analysis of a lower jawbone found in the plateau's Baishiya Karst Cave recently confirmed that the bone was Denisovan. Estimated by radioisotopic dating to be at least 160,000 years old, the jawbone section is the earliest sign of hominins in the region and predates evidence for modern humans on the Tibetan Plateau by about 30,000 to 40,000 years, scientists reported in a new study. [Denisovan Gallery: Tracing the Genetics of Human Ancestors]

Found in 1980 at an altitude of over 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), the jawbone portion contains two large molars, and was so well-preserved that scientists were able to model a virtual "mirror" of the existing half to create a complete lower jaw.

Their examination showed that the bone came from a population that was closely related to the Denisovans found in Siberia. Its location also addressed a long-standing mystery about Denisovans' genetic legacy.

The Siberian Denisovans' genetic makeup included adaptations for living at high altitudes — but the altitude of the Siberian cave was only 2,297 feet (700 m). The discovery of the jawbone on the Tibetan Plateau shows that Denisovans were already living at extreme altitudes 160,000 years ago, and were adapted to low-oxygen environments, according to the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And they did so "long before the regional arrival of modern Homo sapiens," study co-author Dongju Zhang, an archaeologist with the Lanzhou University in China, said in a statement.

Though Denisovan fossils have been found in only two locations, some Denisovan DNA is retained in contemporary populations of Asian, Australian and Melanesian people, said Jean-Jacques Hublin, a study co-author and director of the Department of Human Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

This hints that the ancient hominin group was likely more widespread than fossil evidence suggests, Hublin said in the statement.

The findings were published online May 1 in the journal Nature.

- In Photos: Bones from a Denisovan-Neanderthal Hybrid

- In Photos: New Human Relative Shakes Up Our Family Tree

- In Photos: Neanderthal Burials Uncovered

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular