Mystery Sea Opened Up During the Antarctic Winter. Now, Scientists Know Why.

A swath of ice-free sea that regularly opens up during the frigid Antarctic winters is created by cyclones.

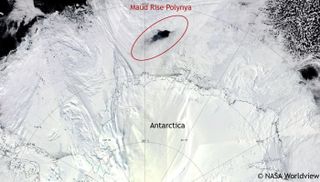

Sea ice in Antarctica is thickest in the winter, so the appearance of open water is perplexing. These open seas are called polynyas. In 2017, scientists spotted one in the Lazarev Sea, which they called the Maud Rise polynya because it sits over an ocean plateau called Maud Rise.

Now, researchers led by Diana Francis, a New York University Abu Dhabi atmospheric scientist, find that cyclonic winds push ice in opposite directions, causing the pack to open up and expose open sea. [Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)]

Polar storms

In mid-September 2017, the Maud Rise polynya was 3,668 square miles (9,500 square kilometers) in size. By mid-October, it had grown to 308,881 square miles (800,000 square km).

An analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery explained the rapid growth. Warm, moist air flowing in from the western South Atlantic hit cold air headed northward from the south, setting the stage for violent storms. The resulting cyclones rated 11 on the Beaufort storm scale, meaning they involved wind speeds of up to 72 mph (117 km/h) and waves up to 52 feet (16 meters) high anywhere they encountered open sea.

These swirling winds pushed ice away from the cyclonic centers, Francis and her colleagues wrote April 24 in the journal JGR Atmospheres.

Cyclones and climate

Polynyas aren't new or necessarily harmful. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), they can provide important ocean access for Antarctic animals and habitat for phytoplankton.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, polynyas may change in a warming future, Francis and her colleagues speculated. Antarctica is expected to experience stronger cyclones as the climate changes, because models show that storms are likely to form more often toward the poles and to be more intense, according to the NSIDC.

If those predictions are correct, Antarctica might see more open water in future winters.

- Antarctica Photos: Meltwater Lake Hidden Beneath the Ice

- In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time

- Icy Images: Antarctica Will Amaze You in Incredible Aerial Views

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.