Fossil 'Death Pit' Preserves Dino Extinction Event … But Where Are the Dinosaurs?

The New Yorker recently described a so-called dinosaur graveyard as holding the remains of an astonishingly diverse trove of dinosaur fossils, including hatchlings; it caused quite a buzz in the media. But even though the site is potentially groundbreaking, the New Yorker article is out of step with the study describing the find.

There's no question that the site in North Dakota (part of the fossil-rich Hell Creek Formation) is an incredible paleontology bonanza; crammed with Cretaceous fossils that were all buried at once, it offers an unprecedented snapshot of the minutes and hours following the asteroid impact that extinguished much of life on Earth around 66 million years ago.

On March 29, prior to the study's publication in a scientific journal, The New Yorker reported that the site contained fossils of pterosaurs, mammals and "almost every dinosaur group known from Hell Creek." However, the study — published online Monday (April 1) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — makes no mention of dinosaurs, apart from an isolated and incomplete hip bone. [Crash! 10 Biggest Impact Craters on Earth]

"There seems to be a disconnect between what is described in The New Yorker with what is actually in the peer-reviewed paper," Stephen Brusatte, a reader in vertebrate paleontology at the School of Geosciences at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email.

Brusatte, who was not involved in the new study, said that the claim would be "awesome" if it were true, but for now, the data simply isn't available.

"I hope there are other dinosaur fossils at the site, and I look forward to hearing more about them," he said.

Lead study author Robert DePalma, who conducted the research as a doctoral candidate in geology at the University of Kansas (KU), told Live Science that "the only information that anyone should be talking about is what's in this published paper, because that's the only thing that can be freely evaluated based on the scientific data."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Densely packed fossils

The Cretaceous period (145.5 million years ago to about 65.5 million years) literally ended with a bang. Scientists cite a massive asteroid impact in waters near Chicxulub, Mexico, as the prevailing explanation for the sudden disappearance of most of Earth's animal species — including all dinosaurs except birds.

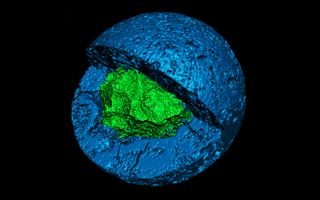

When the asteroid struck, it ended the Cretaceous and ushered in the Paleogene. The newly described site lies between layers of Cretaceous and Paleogene rocks at the Hell Creek Formation, one of the world's richest fossil deposits, which spans parts of Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota. The site contains densely packed fossils of animals that died at the same time "on the last day of the Cretaceous," said DePalma, who is currently a researcher at the KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, and an adjunct professor at Florida Atlantic University.

"Their presence there, and the presence of all the other details in sediments, is helping us to tease out all the little, tiny details that occurred in the first moments after the impact that were unclear before this discovery," DePalma said.

DePalma dubbed the site "Tanis" after the city that hid the ark of the covenant in the film "Raiders of the Lost Ark," according to The New Yorker. The fossil deposit appears to contain something equally as remarkable and unprecedented as its namesake: evidence of mass death directly linked to the Chicxulub impact.

Fish and ammonites

In the study, DePalma and his colleagues described a deposit about 3 feet (1.3 meters) thick, holding fossil evidence of freshwater fish, marine vertebrates, ammonites (extinct relatives of today's nautilus), vegetation and animal-made burrows.

More than 50 percent of the freshwater fish at Tanis died with tiny glass balls called spherules embedded in their gills; in fact, the site was riddled with spherules ranging in diameter from 0.01 to 0.06 inches (0.3 to 1.4 millimeters).

Also known as tektites, these glass beads formed from droplets of melted rock that were sprayed into the atmosphere after the asteroid's impact. These objects rained down on North America minutes later, and the Tanis fish probably inhaled and choked on the tektites before a wave of debris buried the creatures, the researchers reported.

Researchers also found spherules embedded in amber adhering to bits of branches and tree trunks; the amber coating prevented these tektites from deforming and preserved their original shapes. The glass beads are "geochemically nearly indistinguishable" from glass found at the Chicxulub site, and thereby "directly correlate with the Chicxulub impact," the scientists wrote in the study.

In the marine area around the Chicxulub impact, spherules are commonly found "many layers below the mass extinction and many layers above it," Gerta Keller, a professor of geosciences at Princeton University, told Live Science. Kelly, who was not involved in the study, explained that storms or a drop in sea level can shift spherules into younger geologic deposits, so that they appear to have originated there — even if they are older than the rocks around them.

But at Tanis, spherules were stuck in amber and in the gills of dead fish, suggesting that spherules and fish were all buried at the same time, the study said. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Mass Extinctions]

A deadly surge

After the rain of tektites, the water came. Clues in Tanis' sediments and in the positions of the buried fossils hinted that an enormous wave more than 34 feet high (11 m) surged into the river valley from the nearby sea. Sand and mud carried by the wave swiftly buried animals and plants at Tanis, DePalma said.

The surge swiftly traveled inland, flowing from west to east — the opposite direction of the ancient river's flow — so the scientists quickly ruled out typical river flooding as the cause of mass death, DePalma said. Only a tsunami or a seiche, a towering wave that forms in large bodies of water, could create the deposit that the scientists found. It was likely caused by the seismic waves generated by the Chicxulub asteroid, the researchers reported.

Dozens of sites around the globe exhibit a geologic layer marking the end of the Cretaceous. That layer, rich in spherules and minerals that drifted to Earth after the asteroid impact, draws a stark division between global diversity as the Cretaceous was winding down and the dramatic disappearance of numerous plant and animal species that followed, Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., told Live Science.

What makes the Tanis site exceptional is that it preserves a moment in time "during the catastrophe itself," as the disaster unfolded 66 million years ago, said Johnson, who was not involved in the study.

"That's the incredible thing about this — it gives you some texture on what was happening on that day when the asteroid hit," Johnson said.

Tanis has only begun to yield its long-buried secrets — to the study authors and other research teams, DePalma said. The mass extinction that followed the Chicxulub impact wasn't the first in Earth's history, and it likely won't be the last; nevertheless, the Tanis site offers a rare perspective on what can happen during a global extinction event, which could inform how we cope with similar challenges to come, DePalma said.

"If we can understand how the world responds to things like that, we can understand how we might begin to deal with an extinction-level event today," he said.

- Meteor Crater: Experience an Ancient Impact

- The 10 Best Ways to Destroy Earth

- When Space Attacks: 6 Craziest Meteor Impacts

Editor's Note: The article was updated to reflect Robert DePalma's affiliation at the time that the research was conducted.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.