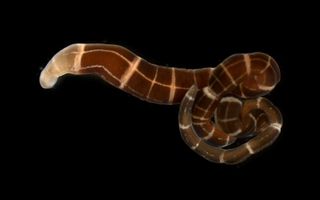

Decapitated Worms Regrow Their Brains

For some worm species, decapitation is no big deal — they just grow a new head.

But far from this superpower being an ancient skill, a recent study suggests that this ability is a relatively recent adaptation, at least evolutionarily speaking.

Regeneration is unusual in animals, but the species that can do it are sprinkled throughout the animal kingdom, and include sea stars, hydras, fish, frogs, salamanders and spiders, as well as worms. Regrowing body parts was long thought to be an ancient trait, with diverse animals tracing the ability to a distant shared ancestor that likely emerged hundreds of millions of years ago.

But for some species of marine ribbon worms, the capacity to regrow severed heads and brains traces back to only 10 million to 15 million years ago — making it a far more recent adaptation than previously thought, scientists found. [In Photos: Worm Grows Heads and Brains of Other Species]

In the study, researchers compiled data on 35 species of ribbon worms in the phylum Nemertea, snipping heads and tails from individuals in 22 species. They discovered that all of the species could regrow an amputated tail, "but surprisingly few could regenerate a complete head," the scientists wrote in the study. (All of the headless worms did survive for weeks or months after their decapitation, however.)

Five species of worms were documented regrowing heads and brains: four of them seen doing so for the first time, and one that was previously known for head regeneration. In addition, the researchers found further evidence in earlier studies of head-growing in three more ribbon worm species.

Their results show that the ancestor of all ribbon worms likely couldn't regrow a severed head, and that head-growing arose independently in only a handful of worm species. This also raises important questions about all animals that can regenerate body parts, the researchers wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When we compare animal groups we cannot assume that similarities in their ability to regenerate are old and reflect shared ancestry," study co-author Alexandra Bely, an associate professor of biology at the University of Maryland, said in a statement.

The findings were published online March 6 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

- Photos: One Worm, Five Shape-Shifting Mouths

- Image Gallery: Catalog of Strange Sea Creatures

- Deep-Sea Creepy-Crawlies: Images of Acorn Worms

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular