19th-Century American Whalers Defaced Rock Art in Australia with Their Own Carvings

Indigenous people in Australia created many thousands of symbolic rock carvings, but archaeologists recently found that 19th-century whalers also left engraved messages for posterity — on some of the same rocks.

Scientists were studying the rock art left behind over thousands of years by indigenous carvers in northwestern Australia's Dampier Archipelago when they made the unexpected discovery: American whalers who traveled to two islands in the archipelago also carved graffiti on the islands' rocks.

And the sailors did so on top of existing aboriginal artwork, according to a new study. [In Photos: The World's Oldest Cave Art]

Whaling ships from America, Great Britain, France and colonial Australia regularly visited the Dampier Archipelago during the 19th century. But their impact on aboriginal communities has been largely overlooked, lead study author Alistair Paterson, a professor of archaeology at the University of Western Australia, said in a statement.

The whalers hunted sperm whales and migrating humpback whales and often anchored in the archipelago's bays for months at a time, according to the study.

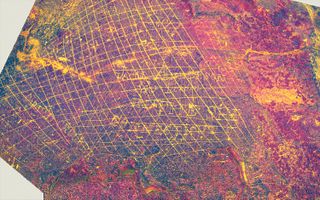

Approximately 1 million indigenous carvings, also known as petroglyphs, are distributed around the archipelago's 42 islands and on the Burrup Peninsula, with some carvings dating to 50,000 years ago. Ancient rock art on the peninsula is currently under consideration for a World Heritage listing, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported in 2018.

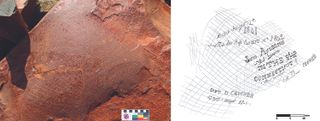

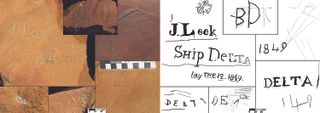

Scientists recently discovered samples of engravings representing one or more "artists" from two vessels that sailed to Australia from the U.S. Sailors on the Connecticut left a carved message on Rosemary Island in 1841, and sailors on the Delta carved a missive on West Lewis Island in 1849.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Connecticut inscription includes the words "Sailed August 12, 1841"; the ship's name; and the names "Jacob Anderson" and "Capt. D. Crocker." Aboriginal art in the shape of a grid already scored the rock that the whalers carved, the study authors reported.

Closer inspection revealed that another indigenous grid was added on top of the whalers' carving, perhaps an act of resistance by aboriginals against "the newcomers and their marks," the study said.

On West Lewis Island, the rock chosen by whalers was already covered with petroglyphs, the scientists wrote. One or more whalers carved the date, the ship's name, the names of crewmembers ("J. Leek" and the initials "B.D.) and a rope-wrapped anchor motif.

Whalers may have interacted with indigenous locals after mooring in the island harbors and going ashore for food and other resources. These two carvings are the first evidence of "this earliest phase of white colonisation" in Australia, the scientists wrote.

The researchers also noted that the whalers didn't necessarily have to write on top of the indigenous art. The engraved rocks had smooth and unmarred areas that would have provided a much better surface for easily engraving a message.

This suggests that the whalers chose the location for their carvings deliberately. However, it is unknown if the sailors intended disrespect toward aboriginal culture or if they merely chose to mark their presence in a place that was clearly already designated as culturally and socially important, the study authors said.

The findings were published online Feb. 18 in the journal Antiquity.

- Photos: Prehistoric Rock Art Hints at Elite Class on Kisar

- Photos: Ancient Rock Art of Southern Africa

- Gallery: Amazing Cave Art

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.