Why an Outlaw Was Stabbed to Death and Then Buried Face-Down in Medieval Sicily

In medieval Sicily, a man was stabbed multiple times in the back, buried in a really weird way and ostensibly lost to history.

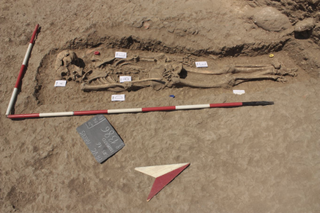

Now, hundreds of years later, archaeologists have excavated evidence of this ancient crime in the Piazza Armerina, Sicily. The researchers found the man's skeleton lying face-down in a shallow pit, empty of any funerary objects typical of ancient burials. The body was buried in a position that was unusual for that time period, they reported last month in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

The evidence suggests that the man, lived in the 11th century and was between 30 and 40 years old when he died. Using CT scans and 3D reconstructions, the researchers set out to determine how he died and why his burial was so unusual. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

According to the report, there was evidence of six cuts on the individual's sternum (breastbone) that were indicative of stab wounds likely inflicted by a knife or dagger. On the right side of his sternum, the researchers found a chop mark where a piece of the bone had been removed, likely by a twisting motion from the weapon.

There was no evidence of other injuries on the man's vertebrae or ribs that would suggest that the man was involved in some kind of "uncontrolled" fight, said lead author Roberto Miccichè, an archaeologist at the University of Palermo in Italy.

The goal of the man's killer, it seems, was to attack the victim in a "very effective and rapid way," Miccichè said; in addition, the assailant likely knew human anatomy "very well." In fact, the cuts were so clean and smooth, that the man may have been immobilized, perhaps with binding, Miccichè said. The man's feet were also squished together in the burial space, which further supports the idea that his feet were bound together.

Using CT scans, the researchers were able to determine the the angle and size of the man's stab wounds, information that the investigators then used to create a 3D reconstruction of where the sharp object dug into the sternum and chest cage.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because the blade of the knife would have entered the man's upper back at an angle, the researchers think that the man was kneeling on the ground at the time of the stabbing, Miccichè said. Since the knife pierced through the thorax (the part of the body between the neck and the abdomen) and into the man's breastbone, Miccichè said the weapon likely punctured the man's lung and heart repeatedly — so he probably died very quickly.

And then there's the weirdness of the burial — the first, well-documented case of a deviant burial in Sicily.

"The burial is atypical because [it] does not follow any religious prescription in the arrangement of the body," Miccichè said. During this time in Sicily, three major monotheistic religions coexisted: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Each had different traditions in burying its dead — Jews and Christians of the Middle Ages buried their dead face-up, while Muslims buried the body lying on its right side, so that the head faced southeast, toward Mecca.

This skeleton, on the other hand, was buried face-down.

Atypical burials tend to be the result of superstitious beliefs (such as if people think the dead person is a vampire or has returned from the dead) or an indication that the person was an outlaw, Miccichè said. He said he thinks, in this case, that it's the latter. If in "his life, the individual was not aligned to the social order of the community, [his] burial should reflect this lack of conformity in death," Miccichè said.

All of this is to say that the man was likely an exile of sorts who was executed.

What's more, this was a time of "crisis and social reorganization" that occurred right after the Norman conquest of Sicily in 1061. "As everywhere and anytime during a period of sociopolitical rearrangement, it is possible to note an increase in violent acts among people," Micciché said.

Now, Miccichè and his team are looking through medieval archaeological records to find evidence of weapons that could be compatible with the marks on the skeleton and move a step closer to solving this ancient game of Clue.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 12:23 p.m. on Feb. 21 to correct when the time of crisis occured. It was right after the Norman conquest of Sicily, not the Norman conquest of England.

- The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Image Gallery: A Medieval Knight's Kin

- 5 Real-Life Inspirations for 'Game of Thrones' Characters

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.