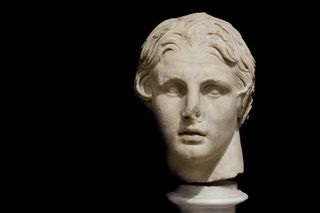

Why Alexander the Great May Have Been Declared Dead Prematurely (It's Pretty Gruesome)

Alexander the Great may have been killed by Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological condition in which a person's own immune system attacks them, says one medical researchers.

The condition may have led to a mistaken declaration of the king's death and may explain the mysterious phenomenon in which his body didn't decay for seven days after his "death."

Alexander the Great was king of Macedonia between 336 and 323 B.C. During that time, he conquered an empire that stretched from the Balkans to modern-day Pakistan. In June 323, he was living in Babylon when, after a brief illness that caused fever and paralysis, he died at age 32. His senior generals then fought each other to see who would succeed him. [Top 10 Reasons Alexander the Great Was, Well ... Great!]

According to accounts left by ancient historians, after a night of drinking, the king experienced a fever and gradually became less and less able to move until he could no longer speak. One account, told by Quintus Curtius Rufus, who lived during the first century A.D., claims that Alexander the Great's body didn't decay for more than seven days after he was declared dead, and the embalmers were hesitant to work on his body.

Ancient historians reported that many people believed that Alexander the Great was poisoned, possibly by someone working for Antipater, a senior official of Alexander's who was supposedly quarreling with the king. In 2014, a research team found that the medicinal plant white hellebore (Veratrum album) could have been used to poison Alexander.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Based on the symptoms recorded by ancient historians, Katherine Hall, a senior lecturer in the Department of General Practice and Rural Health at the University of Otago in New Zealand, believes that it's possible that Alexander actually died of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The condition, Hall said, may have left Alexander in a deep coma that may have led doctors to declare, mistakenly, that he was dead, something that would explain why his corpse supposedly didn't decompose quickly, noted Hall in her paper published recently in the journal Ancient History Bulletin. [Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families]

The syndrome "is an autoimmune disorder where the patient's own immune system has become confused in differentiating between an invading organism, such as a bacteria, virus, or (very rarely) vaccine products, and the patient's own body," Hall wrote in her paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While globally it occurs in, at most, one out of every 25,000 people per year, the incidence rate is higher in modern-day Iraq, particularly during spring and summer, Hall wrote in her paper, noting that Babylon is in modern-day Iraq and that Alexander died in June.

There are several more clues that point to Guillain-Barré syndrome in Alexander's death, Hall wrote. "The most striking feature of Alexander the Great's death is that, despite being extremely unwell, he was reported to have remained compos mentis [sane] until just before his death," she wrote, noting that this is something seen in people suffering from Guillain-Barré . The gradual paralysis that Alexander supposedly experienced is also seen in patients with that syndrome.

Reactions

Live Science talked to several scientists not involved with the research who discussed their thoughts on Hall's claim.

It's "an interesting idea" that Alexander was killed by Guillain-Barré syndrome said Hugh Willison, a professor at the University of Glasgow College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation. "Although from the historical evidence available, it is not possible to establish this with any degree of certainty," he added.

Another professor, Michael Baker, said: "Based on a quick scan [of the article] I think the theory is quite plausible," Baker, a professor in the Department of Public Health at the University of Otago, told Live Science. To say anything more definitive, Baker said he'd need more time to review the paper.

The theory is "very interesting," said Pat Wheatley, a professor of classics at the University of Otago. Hall took some of Wheatley's classes, and the two have been discussing the theory for about a year, Wheatley said. However, Wheatley urged caution when looking at the accounts left by ancient historians, noting that the surviving accounts date to well over a century after Alexander's death, and some of the details may be inaccurate. Still, the "the theory is certainly worth floating," Wheatley said.

- Bones With Names: Long-Dead Bodies Archaeologists Have Identified

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Gallery: In Search of the Grave of Richard III

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Most Popular