100-Million-Year-Old Hagfish Complete with Slime Kit Discovered

Eyeless, jawless hagfish — still around today — are bizarre, eel-like, carrion-eating fishes that lick the flesh off dead animals using their spiky tongue-like structures. But their most well-known feature is the sticky slime that they expel for protection.

And now, scientists know that hagfish slime is robust enough to leave traces in the fossil record, finding remarkable evidence in a fossilized hagfish skeleton excavated in Lebanon. This new discovery is also prompting researchers to redefine the hagfish's relationship to other ancient fish and to all animals with backbones. [Photos: The Freakiest Looking Fish]

Hagfish fossils are scarce, and this specimen — an "unequivocal fossil hagfish" — is exceptionally detailed with lots of soft tissue preserved, scientists reported in a study published online today (Jan. 21) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The fossil dates to the late Cretaceous period (145.5 million to 65 million years ago), and measures 12 inches (31 centimeters) in length. Researchers dubbed it Tethymyxine tapirostrum: Tethymyxine comes from "Tethys" (referencing the Tethys Sea) and the Latinized Greek word "myxnios," which means "slimy fish." Tapirostrom translates as "snout of a tapir," and refers to the fish's elongated nose, the study authors wrote.

"A swimming sausage"

Hagfish have been around for about 500 million years, yet there is next to no trace of them as fossils, primarily because their long, sinuous bodies lack hard skeletons, said lead study author Tetsuto Miyashita, a postdoctoral fellow with the Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago.

"Basically, it's like a swimming sausage," Miyashita told Live Science. "It's a bag of skin with a lot of muscles in it. They don't have any bones or hard teeth inside them, so it's really difficult for them to get preserved into the fossil record."

When threatened, modern hagfish produce a type of mucus from special slime glands distributed along their bodies. As keratin fibers — the stuff that makes up our fingernails and hair — in the mucus encounter water, they tangle and expand the slime glob to about 10,000 times its original size in just a few tenths of a second, researchers reported in another study, published Jan. 16 in the journal Royal Society Interface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hagfish slime is a sticky mess that deters predators by clogging their gills, and this slimy defense is even effective on land, as a number of unlucky motorists learned in 2017. Copious, gooey hagfish slime temporarily shut down part of a highway in Oregon, after a truck overturned and dumped its payload of hagfish — 7,500 pounds (3,400 kilograms) — onto the road.

And now, scientists know that this slimy defense was in place 100 million years ago, perhaps used to deter Cretaceous marine carnivores such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and ancient sharks, Miyashita said.

Slime scans

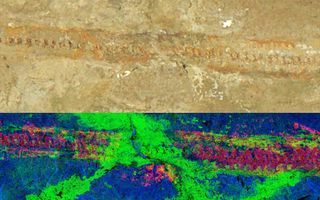

The PNAS study authors examined the hagfish fossil using synchrotron scanning — a type of imaging technology that bombards objects with highly energized and polarized particles — and they detected chemical signatures of keratin fibers concentrated in more than 100 places.

Its presence in the fossil suggested that ancient hagfish during this period had already evolved their slimy superpower, according to the study.

This rare find also provides a clearer picture of where these oddball, slime-producing fish belong on the tree of life, perhaps helping to settle a scientific debate spanning centuries, Miyashita said.

Hagfish are so weird that they have long been seen as "the odd ones out" on the fish family tree, the sole occupants of a lonely branch, Miyashita said. Because their fossils are so scarce, it's unclear how long ago hagfish diverged from the common ancestor they shared with all other fishes (and subsequently, all vertebrates).

But the new fossil shows that hagfish 100 million years ago were remarkably similar to hagfish today, suggesting that their specialized features accumulated gradually over time. If so, rather than being a more primitive "cousin" to other fish, hagfish should be grouped together with long-bodied lampreys, the study authors reported. In clarifying these relationships, scientists develop a more detailed picture of how creatures with backbones evolved, Miyashita said.

"Where we place hagfish makes a difference to how we think about our own ancestors, more than 500 million years ago," he added.

- Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures

- Goopy Science: How to Make Slime with Glue

- Biomimicry: 7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular