The Appendix May Be Linked to Parkinson's Disease. But Don't Run Out and Have Surgery.

Parkinson's disease, a degenerative neurological disorder that impairs brain cells and causes movement problems, could have its origins in the appendix, a new study suggests. The vestigial organ, the researchers say, could be the source of proteins that can find their way to the brain and once there, extend a deadly grip on nerve cells.

According to the study, published yesterday (Oct. 31) in the journal Science Translational Medicine, people who had their appendix removed when they were young were 19 to 25 percent less likely to develop Parkinson's later in life.

The new study — though not the first to suggest that Parkinson's can start in the gut, or even in the appendix — was one of the largest ones done to date. The research "further supports the notion that [Parkinson's] starts in the gut," Dr. Ted Dawson, a professor of neurodegenerative diseases at Johns Hopkins University who was not part of the study, told Live Science.

In the first part of the study, the researchers sifted through two large databases — one that contained information on more than 1.6 million people in Sweden, and the other with data on 849 international patients who had Parkinson's disease. Both databases indicated which people had had their appendixes removed. [10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp]

They found that people who had their appendixes removed were 19 percent less likely to develop Parkinson's later in life, but only if they had the procedure done early — decades before the typical onset of the disorder. What's more, people in the study who did end up developing Parkinson's did so, on average, 3.6 years later if they had their appendixes removed than people who still had their appendices.

The findings suggest that the appendix "might be important in the early events or possibly in the initiation of this disease," said senior author Viviane Labrie, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Van Andel Research Institute in Michigan.

Labrie and her team also found that people who had undergone an appendectomy (surgery to remove the appendix) and lived in rural areas were 25 percent less likely to develop Parkinson's than those who had the surgery and lived in urban areas. Parkinson's is often more common in rural areas, which may be due to exposure to pesticides that are thought to be linked to the disease, Labrie said. This association wasn't present in those who were genetically predisposed to Parkinson's, the researchers noted. (Only about 10 percent of people with Parkinson's are genetically predisposed.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's going on down there?

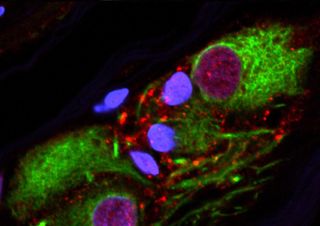

A telltale sign of Parkinson's in the brain are "Lewy bodies" — large deposits of proteins that form around neurons and hinder their release of chemicals or neurotransmitters that instruct our movement and thoughts. These Lewy bodies are mostly made up of abnormally shaped or "clumped" proteins called alpha-synucleins.

In the second part of the study, Labrie and her team set out to look for these clumps of proteins in the appendix. They imaged 48 appendixes taken from people without Parkinson's. The appendixes had been taken from both young and old patients. Some were inflamed and some were not (gut inflammation is considered a potential risk factor for Parkinson's).

They found that all the appendixes had contained the protein clumps. In other words, the same proteins that wreak havoc in the brain seem to be normal in the appendix. This suggests that "what's present in the appendix" could actually be a "seed" that could travel from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain and cause Parkinson's, Labrie told Live Science. (However, the study couldn't ultimately prove that this is the cause of the disease.)

It's unclear why the appendix has these clumps in the first place, however. The appendix, though largely — and erroneously — thought to be useless in the body, contains a number of immune cells and helps to identify and monitor pathogens and raise red flags (immune responses) when it finds them, Labrie said.

So perhaps these clumps "might also be involved in immune function," Labrie said.

Preventative appendectomies? No

Still, the findings don't mean people should run out and schedule appendectomies. Parkinson's itself is a relatively rare disease that affects less than 1 percent of the population.

"One of the things that we don't want to get across to people is that [they] should be having preventative appendectomies or that just because you have an appendix, you're going to get Parkinson's disease," Labrie said. Rather, possible future preventative treatments could aim to target levels of the clumped proteins in the gut, or to somehow prevent their escape to the brain.

In addition, the researchers only looked at the appendix in this study, but there could be other places in the GI tract that also have these clumps "that we just haven't looked at yet," Labrie said.

Now, Labrie hopes to understand the molecular basis of what's going on: If these clumps of proteins can't distinguish a healthy appendix from one that may seed Parkinson's, are there other biological markers that can?

It's clear that the gut whispers to the brain, the brain whispers to the gut and together they turn the cranks and wheels of our bodies — a conversation that continues to remain largely mysterious to us.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular