Lost Chain of Underwater Volcanoes Is a Massive Whale Superhighway

Thanks to an especially slobbery "Looney Tune," the island of Tasmania is best-known for its eponymous devils. But the nearby Tasman Sea is no less rich in oddball biodiversity. Take, for example, the newest discovery reported by the Australian research vessel the Investigator. A team of seafaring scientists has uncovered an ancient highway of massive underwater volcanoes — and those submerged mountains (or "seamounts") are apparently brimming with whales, according to a news release from Australia's national science agency. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

"While we were over the chain of seamounts, the ship was visited by large numbers of humpback and long-finned pilot whales," Eric Woehler, a seabird ecologist at the University of Tasmania and a crewmember aboard the Investigator during its recent expedition, said in a statement. "We estimated that at least 28 individual humpback whales visited us on one day, followed by a pod of 60 to 80 long-finned pilot whales the next."

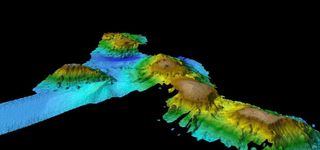

Once the Investigator had sailed about 250 miles (400 kilometers) east of Tasmania, the crew saw spikes in phytoplankton activity. Sonar scans revealed that the activity coincided with the appearance of a gargantuan chain of volcanic mountains submerged thousands of feet below the surface of the sea.

Sonar scans revealed that these hidden, underwater mountain ranges rose up from the seafloor beginning about 3 miles (5,000 meters) below the water's surface. The mounts varied in size and inclination; some were jagged peaks that stabbed up to 2 miles (3,000 m) above the seafloor, while others were vast, low plateaus. But each of the titanic hills and valleys likely formed many millennia ago as a result of ancient volcanic activity in the area, the researchers said.

Today, that variety of terrain likely provides habitats for a hugely diverse population of marine life. The jutting mounts could serve as underwater "signposts" on a migratory highway for regional whales, helping to guide them from their winter breeding grounds to their summer feeding grounds, Woehler said. In addition to the plentiful phytoplankton and whale sightings, the Investigator crew also reported seeing a significant variety of seabirds, including four species of albatrosses and petrels.

"This is a very diverse landscape and will undoubtedly be a biological hotspot that supports a dazzling array of marine life," said Tara Martin, a researcher with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), the Australian science agency that owns and operates the Investigator.

Researchers will have to study these newly discovered seamounts further to find out if they are indeed what Woehler called a "highway of marine life." Two fresh expeditions to the area are set to embark in November and December. In these trips, the team plans to bring back high-resolution video of the sea life swarming on and around the ancient seamounts. Stay tuned for the footage on the Investigator's website.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.