Meet the Extinct Cow with a 'Bulldog' Skull

Nobody would ever say to this cow, "Why the long face?"

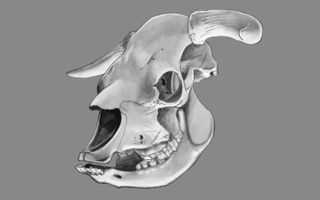

The snub-nosed cow, known as a Niata, is a now-extinct breed of domesticated cattle once found in South America. Its shortened, broad profile, unique in cows, was more reminiscent of a bulldog than a bovine; it had a dramatically flattened face and a significant underbite, much like contemporary dog breeds such as pugs, bulldogs and boxers. Naturalist Charles Darwin wrote about Niata cows in 1845, after seeing them for the first time in Argentina. Though their bizarre head shape generated much discussion in the decades that followed, their biology was not well understood.

Recently, scientists conducted the first analysis of the Niata cow's anatomy and genetics, to find out whether the animal's shortened jaw and skull affected its ability to eat and breathe, possibly contributing to the breed's extinction. [Heritage Livestock Are Vanishing Across the United States (Photos)]

Extreme skull shapes in dogs have been linked to severe health issues, and researchers wondered whether the extremely flattened skulls of Niata cows created similar problems.

"Many changes brought by domestication are not necessarily advantageous," study co-author Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra, an associate professor at the University of Zurich, told Live Science in an email.

In the new study, the scientists examined Niata cow skeletons in museum collections using methods that were unavailable to 19th century naturalists, such as noninvasive imaging and DNA analysis. They also looked at skull function using biomechanics, an engineering-inspired approach that examines the mechanical structures and functions of biological systems.

Shaped by genetics, not disease

Prior research proposed that the Niata's flattened skull shape was caused by a condition called chondrodysplasia, which affects bone and cartilage growth and produces shortened limbs and faces.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But when the scientists examined Niata skeletons, they found that the cows' legs were not short relative to their body size. Genetic evidence told the researchers that Niata cows were a "true breed"; their shortened skulls were not the result of disease, but rather a persistent trait that distinguished them from other breeds. And this trait would be retained in a lineage, even if the cows interbred with other types of cattle, according to the study.

The cows didn't appear to suffer impairment to breathing or eating from their short faces, either, as some types of dogs do, the study authors reported. X-ray imaging revealed that head shape did not affect their nasal openings, and digital computer models of the cows' skulls with jaws in motion showed that Niatas experienced less stress on their skulls during chewing than other cows did.

It's therefore unlikely that Niata cattle went extinct because the breed was unfit, the researchers said. Niata cattle disappeared from Argentina at a time when cattle raising was gaining momentum, and it's likely that the more-esoteric breeds — such as the Niata — were abandoned in favor of "the optimal breed," Sánchez Villagra said in a statement.

"This meant that fewer breeds were exploited and many became extinct," he said. "This has happened with many species of domesticated animals, which has resulted in a decrease of genetic and morphological diversity in the animals closest to our lives."

The findings were published online June 14 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular