See How Brain Worms Turn Ants into the Walking Dead

Can you wrap your mind around the idea of a parasitic worm in an ant brain? If you can't, don't worry — there are photos.

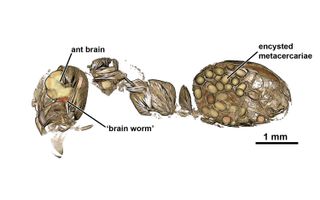

Scientists recently captured the first images showing these "mind-controlling" parasites in action inside an unfortunate ant's head, revealing never-before-seen views of a deadly, brain-dwelling flatworm — the lancet liver fluke (Dicrocoelium dendriticum) — and uncovered clues to the worm's secrets of manipulation and behavior.

Lancet liver flukes target a wide range of ant species. Though they practice their mind-controlling tricks only on ant hosts, they pingpong among multiple species to complete their life cycle, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As eggs, they inhabit the dung of grazing animals like deer or cattle. After infected feces are eaten by snails, the worm larvae hatch and develop in the mollusks' guts. Snails eventually eject the worm larvae in slime balls, which are then gobbled up by ants. [8 Awful Parasite Infections That Will Make Your Skin Crawl]

Inside the ant is where the worm turns. Ants typically ingest multiple worms, most of which lurk in their abdomen. However, one worm makes its way to the ant's brain, where it becomes the insect's driver, compelling it to perform "absurd behaviors," scientists reported in a new study.

Under the worm's control, the now-zombified ant displays a death wish, climbing blades of grass, flower petals or other vegetation at dusk, a time when ants usually return to their nests. Night after night, the ant clings with its jaws to a plant, waiting to be eaten by a grazing mammal. Once that happens, the parasites reproduce and lay eggs in the mammal host. The eggs are expelled in feces, and the cycle begins anew, according to the CDC.

It's all about control

For years, biologists have been intrigued by the relationship between flatworm and ant, but the details of how the parasites manipulated ant behavior remained a mystery, "partly because until now we haven't been able to see the physical relationship between the parasite and the ant's brain," study co-author Martin Hall, a researcher with the Life Sciences Department at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That all changed when a team of scientists looked inside infected ants' heads and bodies using a technique called micro-computed tomography, or micro-CT. This method combines microscopy and X-ray imaging to visualize the inner structures of tiny objects in 3D, and in breathtaking detail.

The researchers decapitated preserved ants, removing their mandibles to get a clearer view inside their heads, then stained and scanned the ants' heads and abdomens, along with one complete ant body, they wrote in the study.

Their scans showed that an ant could have as many as three worms jockeying for control of its brain, though only one worm would eventually achieve contact with the brain itself. Oral suckers helped the parasites latch onto the ant's brain tissue, and the worms appeared to target a brain region associated with locomotion and mandible control.

Hijacking this area of the brain likely enabled the worm to direct the ant's death march and lock its jaws on a grass or flower anchor as it waited to be eaten, the study authors reported.

The findings were published online Tuesday (June 5) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.