No, This Tiny Beast Is Not Half-Mammal, Half-Reptile (But It's Still Super Cool)

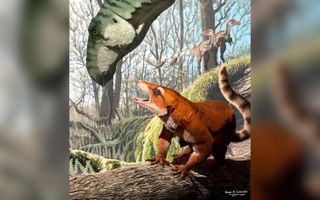

A small, furry animal with a blunt snout and beady eyes scuttled across what is now eastern Utah some 130 million years ago. And while the wee beast was surely unusual and fascinating, there's one thing it was definitely not: half-mammal and half-reptile.

Headlines about the recent find have described it as though it were some bizarre hybrid of reptile and mammal. But while it might be amusing to imagine a beast with the front end of a lizard and the rear end of a rat, it's not very scientific. [Real or Fake? 8 Bizarre Hybrid Animals]

The little animal, which would have stood just 3 inches (7.6 centimeters) tall and weighed about 2.5 pounds (1.1 kilograms), belonged to a group known as the haramiyidans, which emerged during the late Triassic period (251 million to 199 million years ago), and are known mostly from fossil teeth. Scientists have argued over whether haramiyidans were early mammals or a sister group — closely related to mammals, but lacking some features used by paleontologists to decide who's a mammal and who's not.

In a new study describing the tiny skull — which represents a new genus and species of haramiyidan called Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch, and is thought to be between 139 million and 124 million years old — researchers determined that haramiyidans were mammal relatives, though not actual mammals. And though haramiyidans looked a lot like mammals, they retained more "nonmammalian" structures from their distant ancestors than the first true mammals did, the scientists reported. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Both haramiyidans and mammals trace their origins to a group known as the synapsids. All syanpsids last shared a common ancestor with reptiles about 330 million years ago, "so the split between reptiles and mammals runs very deep," paleontologist Elsa Panciroli, who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science in an email.

In other words — mammals don't have "reptile ancestors." Rather, both mammal ancestors and reptile ancestors branched off from a shared common ancestor hundreds of millions of years ago, Panciroli explained.

In the past, scientists might have said that early synapsids shared more features in common with reptiles than with mammals, "but really we need to look at it as being more about which group is more like their common ancestor," said Panciroli, a doctoral candidate studying mammal origins at the University of Edinburgh and National Museums Scotland.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One trait found in reptiles and retained in some modern mammals is egg-laying, seen in platypuses and spiny anteaters. Egg-laying can be traced back to very distant ancestors of the reptilian and mammal lineages. Mammals with placentas, on the other hand, are thought to originate from a shrew-like animal called Juramaia sinensis, which lived about 160 million years ago.

A transitional skull

In life, the newly described Cifelliodon certainly resembled a mammal. It had a furry body and a long tail, teeth that could slice and crush vegetation and tiny eye sockets that suggested its eyes were small and its vision was poor. However, its olfactory bulbs were unusually large, hinting that it relied heavily on its sense of smell, according to the study.

High-resolution X-ray scans also revealed the inner cranium shape, which was "transitional between earlier stem mammals and crown Mammalia," the researchers wrote. This means that Cifelliodon — and other haramiyidans — had some mammal-like features, but not as many as the group that defines mammals alive today.

The exceptional condition of the Cifelliodon skull — particularly its 3D shape — offered clues about the haramiyidan group that had only been guessed at before, when the only available fossils were scanty or crushed flat, lead study author Adam Huttenlocker, an assistant professor of clinical integrative anatomical sciences with the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, told USC News.

"The three-dimensional preservation of Cifelliodon highlights the primitive brain, palate and feeding structure of this special group and reinforces their position near the base of the mammalian family tree," Huttenlocker said.

The findings were published online May 23 in the journal Nature.

Editor's note: This article was updated June 8 with additional information to clarify the ancestral relationship between mammals and reptiles.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular