How 2 Massive Carvings Found Near Egypt Pyramid Were Rescued from Looters

Two massive limestone blocks decorated with hieroglyphs and carved images have been discovered beside the Pyramid of Amenemhat I at Lisht in Egypt.

Archaeologists led by Mohamed Youssef Ali, of Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities, rescued the blocks from looters who were digging near the pyramid in January 2011, a discovery reported recently in the Egyptian Archaeology magazine.

The rescue effort was dangerous, as the archaeologists essentially risked their lives to carry them out of the desert, an act that required both physical grit and ingenuity. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Pharaoh suckling a goddess

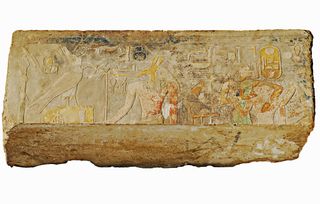

One of the blocks is nearly 5 feet by 2 feet (1.5 by 0.5 meters) and shows pharaoh Amenemhat I (reign circa 1981-1952 B.C.) suckling a goddess identified as the "Wadjet of Buto" in hieroglyphs engraved into the block. The fertility god Khnum stands beside the pharaoh and the goddess, saying, "I give to you water. The entourage of the gods," according to translated hieroglyphs.

The scene suggests that Khnum and the Wadjet of Buto are the parents of pharaoh Amenemhat I, Ali said. The "water" likely symbolizes Khnum's sperm, which impregnates the goddess, allowing for the pharaoh to be born, Ali said. Pharaohs are normally shown as adults and not infants, which may explain why Amenemhat is suckling the goddess even though he is depicted as a grown man, according to Ali.

Ali noted that this block was part of a larger carving. Another block from this carving was discovered at Lisht in 1908 by archaeologists with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That block has an image of the sky god Horus on it and is now on display at the Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 108, according to the Met’s website.

Another mysterious block

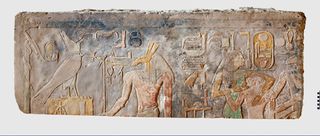

Ali's team also rescued another limestone block near the pharaoh's pyramid in January 2011. That block "shows a group of six foreigners, perhaps Libyan men, with three children," Ali wrote in the Egyptian Archaeology article. The block, which is nearly 5 feet wide and 2 feet high (1.5 by 0.5 meters), likely dates back centuries before the Amenemhat I block, Ali noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The men are bare-chested over short kilts, and have beards and long hair. There are no inscriptions on the block to inform us who these people were, and whether this scene relates to a specific event, such as a war or a trading mission," Ali wrote in the article.

Dramatic rescue

At the time of the rescue, during a revolution in Egypt, Ali was director of Dahshur and Lisht, two archaeological sites to the south of Cairo. [Reclaimed History: 9 Repatriated Egyptian Antiquities]

"It was the first month of the January revolution in Egypt, the ministry of the interior withdrew all the troops from the country, the police station was burned by the revolutionaries and the prisoners escaped from the prison, everything and every place became unsafe in Egypt, everybody was trying to protect his home and his family from the criminals who were escaping from the prisons who attacked the houses for the sake of food, money and sex, too," Ali told Live Science. In this chaos, looters started digging at Dahshur and Lisht.

Ali said he heard that two groups of looters were digging by the Pyramid of Amenemhat I. The two groups were arguing over who should take possession of the looted artifacts, and one of the groups had called the military in hopes of exchanging the blocks for a reward.

It was a dangerous situation. "No one can help me or protect me and my team if I decided to go to Lisht," Ali said. Despite the danger, he and his team, which included two other archaeologists and two unarmed guards, went to investigate.

One of the looters, a young guy who had called the military, guided Ali's team to the place where the two limestone blocks were found. The looter asked Ali about receiving a reward from the government for showing the team the spot holding the limestone blocks. "I answered him, 'Yes, of course you will have a reward,'" Ali said, knowing that the government could not pay an award.

"I was a liar, [but] I had to," Ali said. A government law stipulates that an award could be paid to someone who finds artifacts in their house but not at an archaeological site, Ali said.

Once they had excavated the two blocks, Ali's team decided to take them to a storage facility at Dahshur. However, the car Ali was using couldn't "carry these huge stones, and the other [problem] is the second group of looters waiting for us on the way to Dahshur," Ali said.

This second group of looters, who were unaware that Ali's car could not handle the stones, would be waiting to ambush Ali's team when they left the pyramid.

One of the team members "gave me a very good idea to resolve this problem and secure the monuments and save our souls at the same time," Ali said. "He is from the village [located near the pyramid] and knows a good car used to move the vegetables from the village to the city every day. We hired it and [towed the blocks] upon it and moved to Dahshur; and we left my car in front of the pyramid," fooling the second group of looters into believing the team was still at the pyramid, Ali said.

The plan worked and the team, along with the two blocks, arrived safely at the storage facility in Dahshur.

Ali is the general director at the Ministry of Antiquities and the general director at the Registration Department at the Giza Pyramids.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.