Tonsils: Definition, anatomy & function

Tonsils are small organs in the back of the throat.

Tonsils are a pair of oval-shaped tissues that sit at the very back of the mouth on either side of the throat. These are called palatine tonsils and are usually what people refer to when they describe their tonsils.

However, we have three other types of tonsils, too: the adenoid or pharyngeal tonsil that sits at the back of the naval cavity; a pair of tubal tonsils that sit at the bottom of the auditory canal; and a pair of lingua tonsils that sit at the root of the tongue. Together, all the tonsils make up Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

Related: What is the gag reflex?

What is the purpose of tonsils?

As part of the lymphatic system, tonsils play an important role in protecting the body from harmful pathogens that may be ingested or inhaled. The palatine tonsils act like a goalie for your throat, preventing harmful things from entering the body.

They capture these pathogens and alert the immune system. The tonsils also make their own disease-fighting white blood cells and antibodies, according to the Mayo Clinic.

What do infected tonsils look like?

The palatine tonsils grow throughout childhood and reach their largest size during puberty. They shrink a bit during adulthood and wind up being around the size of a lima bean (about 2.5 centimeters long, 2.0 cm wide and 1.2 cm thick).

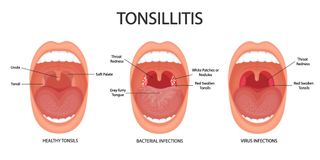

Healthy tonsils have an irregular surface covered with a pink mucosa. Running through the mucosa are tubular channels or pits, called crypts, that run through the entire organ. The crypts are primarily full of dead cells or cellular debris, as described in a 2001 review published in the journal Anatomy and Embryology.

Tonsillitis is what happens when healthy tonsils become infected, most often with a virus but occasionally with a harmful bacterial pathogen, according to the Mayo Clinic. Infected tonsils become swollen and inflamed, causing a sore throat and difficulty swallowing. Tonsillitis can also cause a fever. The condition is most common in children over two, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Strep throat happens when the tonsils are infected by bacteria called Streptococcus, usually classified by two different strains, A and B. Strep is usually a problem that affects children, though adults can get strep throat, too.

During this infection, the tonsils are usually very inflamed, and the person may have white pustules on their tonsils, along with white, stringy pus gathering in the throat. If strep goes untreated, it can cause scarlet fever impetigo, cellulitis, toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease), according to the National Institutes of Health. Rheumatic fever may also occur from an untreated strep infection.

"The inflammatory process can occur soon after a strep infection or weeks later. Many patients don't remember having the initial sore throat. Rheumatic fever can be mild or very serious causing permanent damage to the heart," Dr. Stacey Silvers of the Madison Skin and Laser Center in New York, told Live Science.

The treatment for strep is fairly simple. Typically, doctors will prescribe antibiotics, such as Augmentin, to rid the body of the bacteria. Most other cases of tonsillitis can be treated with at-home cures such as throat lozenges, gargling salt water, drinking plenty of fluids or taking over-the-counter painkillers.

What are tonsil stones?

Tonsil stones are a typical affliction of the throat area as well. This happens when debris gets caught in the groves of the tonsils. The immune system then attacks the debris, creating a rock-like stone. Common symptoms are irritation and redness of the tonsils and occasionally bad breath due the bacteria that accumulates. You may be able to see the tonsil stones if they’ve formed near the surface, but some may form deep in the tissue.

Usually, tonsil stones can be removed with brushing, a water pick or by a dentist. But if they keep coming back, a tonsillectomy, or removal of the tonsils may be necessary.

When should tonsils be removed?

Surgery to remove tonsils due to tonsillitis or other issues was once common practice, but doctors now recommend the operation only in rare or serious cases of tonsillitis or for patients who experience frequent episodes of tonsillitis that are difficult to manage, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Frequent tonsillitis is generally defined as at least seven episodes in one year, at least five episodes a year for two years, or at least three episodes a year for three years.

Removal of the tonsils may also be necessary if the tonsils are oversized and cause problems with proper breathing or sleeping.

In rare cases, a tonsillectomy may also be the best way to remove cancer tissue on or around the tonsils, or prevent recurrent bleeding from blood vessels on or near the tonsils.

"However, this surgery carries risks of anesthesia, pain and bleeding, as well as other risks, thus a decision of this type must be balanced by a risk/benefit discussion," said Dr. Erich P. Voigt, an associate professor of otolaryngology at NYU-Langone Medical Center.

The typical recovery time for a tonsillectomy is between 10 days and two weeks.

Additional resources

- Read more about tonsillitis from Penn Medicine.

- Here are a few tips and questions to ask your doctor if you’re considering tonsil removal from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Learn about the details of a tonsillectomy procedure from the Cleveland Clinic.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kimberly has a bachelor's degree in marine biology from Texas A&M University, a master's degree in biology from Southeastern Louisiana University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is a former reference editor for Live Science and Space.com. Her work has appeared in Inside Science, News from Science, the San Jose Mercury and others. Her favorite stories include those about animals and obscurities. A Texas native, Kim now lives in a California redwood forest.

- Alina BradfordLive Science Contributor