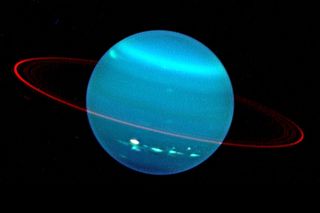

No Joke: Uranus Smells Terrible, Study Says

Uranus smells like rotten eggs, and that is not a joke. A new study finds that the seventh planet from the sun has an upper atmosphere flush with hydrogen sulfide.

Hydrogen sulfide is a gas best known for its repulsive smell; the gas emanates from sewers and volcanoes on Earth, explaining why some hot springs, which are fed by geothermally heated water, smell like breakfast gone bad. Astronomers have now discovered that the gas is common in the cloud tops of Uranus.

That hydrogen sulfide composition is different than what is found in the upper atmospheres of Uranus' fellow giant planets Jupiter and Saturn, where ammonia dominates, said Leigh Fletcher, a study co-author and senior research fellow in planetary science at the University of Leicester in England. Ammonia is made of nitrogen bonded with hydrogen, while hydrogen sulfide is hydrogen bonded with sulfur. [7 Everyday Things That Happen Strangely in Space]

"During our solar system's formation, the balance between nitrogen and sulfur (and hence, ammonia and Uranus' newly detected hydrogen sulfide) was determined by the temperature and the location of the planet's formation," Fletcher said in a statement.

Faint signals

Scientists have long debated the precise composition of Uranus' upper atmosphere, simply because they lacked instruments sensitive enough to detect the gases found there. For the new study, the team used the Gemini North telescope, a 26.5-foot (8.1 meters) telescope that sits on the Mauna Kea volcano in Hawaii. Researchers used the telescope's Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NFIS), first designed to image the outsides of black holes in far-off galaxies, to sample reflected sunlight from Uranus' high atmosphere.

Thanks to that instrument's enormous sensitivity, researchers were able to detect very faint lines on the light spectrum indicating that hydrogen sulfide had absorbed some wavelengths from the sunlight, the scientists said.

"Only a tiny amount [of hydrogen sulfide] remains above the clouds as a saturated vapor," Fletcher said, and this made detection a challenge.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nasty atmosphere

The findings will help clarify how Uranus and its neighboring ice giant, Neptune, formed, the researchers said. They reported their results April 23 in the journal Nature Astronomy. There is likely a more-concentrated reservoir of hydrogen sulfide beneath the cloud deck, the researchers said, but this likely lies beyond Earth-bound telescopes' detection abilities.

However, the clouds on Uranus definitely contain chemicals that a human could detect in person, the researchers said.

"If an unfortunate human were to ever descend through Uranus' clouds, they would be met with very unpleasant and odiferous conditions," study co-author Patrick Irwin, a professor of planetary physics at the University of Oxford, said in the statement. That is, they would if that person miraculously lived to take a whiff.

"Suffocation and exposure in the negative 200 degrees Celsius [minus 328 degrees Fahrenheit] atmosphere made of mostly hydrogen, helium and methane would take its toll long before the smell," Irwin added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular