Renaissance Mapmaker Was a Mastermind and a Copycat

After poring over a stunning, 60-page Renaissance-era map, a scholar has come to the following conclusion: The cartographer who drew the map in 1587 was both a mastermind and a copycat.

And not a very good copycat at that.

"If you look closely at some of the sea monsters, I think it's fair to say that his artistic skills are not great," said Chet Van Duzer, the David Rumsey research fellow at the David Rumsey Map Center at Stanford University. "And it turns out, he was very conscious of that." [Photos: See Images of the Renaissance Map that Sports Magical Creatures]

In fact, the cartographer — Urbano Monte (1544-1613), a nobleman who lived in Milan, Italy — apologized for his poor drawing skills in a treatise he wrote for the map's audience.

"[Monte] mentions some specific sea monsters, and he says, 'These would look a lot better if the hand of the author had even the slightest bit of artistic training,'" Van Duzer told Live Science.

Despite this, the map still charms onlookers and offers clues as to how people viewed the world in the late 16th century. "You feel the author's enthusiasm — let's put it that way," said Van Duzer, who presented his findings about the map at Stanford on Friday (Feb. 23). For instance, Monte depicted the North Pole as four islands and the South Pole as eight.

Fear of empty space

The map center acquired the map in September 2017. Previously, researchers there reported that Monte had enough wealth and status that he didn't have to work, and instead spent his time collecting books and pursuing scholarly interests, Live Science reported in December.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When he was 41, Monte took up cartography and created this world map, replete with mythical creatures, including sea monsters, unicorns and centaurs. Three editions of this map survive today — one at Stanford and two in Italy.

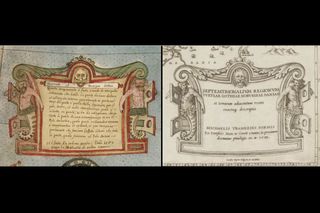

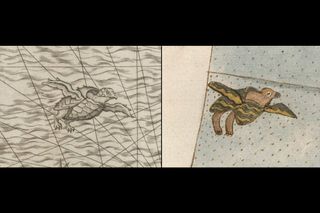

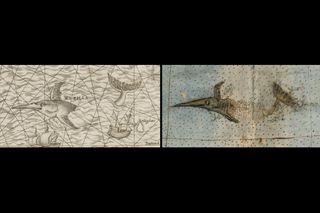

An intensive examination of the Stanford map revealed that Monte was quite the imitator, copying mythical monsters from other world maps, Van Duzer said. For instance, Monte copied an odd-looking turtle bird, a sea monster and a scroll from a map published nearly 30 years earlier by the Italian Michele Tramezzino.

Furthermore, Monte appears to have copied a number of elements from Italian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi's 1561 map. These include a number of sea monsters, a depiction of King Philip II of Spain in a ship and a man beating a dragon, Van Duzer found.

However, it wasn't uncommon for "Renaissance cartographers to 'borrow' from both maps and books, and in some cases to do what we would call blatant copying," Van Duzer said. "Monte was not unusual in that respect."

As to why Monte filled his map with so many monsters, that's likely because of "horror vacui," a Latin phrase that means "fear of empty space," Van Duzer said. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

Creative display

Although he copied his contemporaries, Monte implemented some unorthodox practices. Namely, he left instructions that the 60-page map be arranged like a giant poster and rotated around a pivot point as a 2D disc. Also, he drew the map from the perspective of a bird's-eye view of the North Pole.

It's possible that Monte got the idea of a moving map from a particular edition of Ptolemy's "Geography" that had modern commentary in it, Van Duzer said. The commentary noted that if a map is large, then viewers can't just move their eyes or heads to see it; rather, they need to move their entire bodies. Monte's map is large — a digital version of it on display at Stanford is 10 feet by 10 feet (3 by 3 meters) — and he likely wanted to make it easy for the viewer to see it, Van Duzer said.

But where did he get the idea to rotate it? "There are several possibilities, but I think the most likely one is that he got the idea from a globe," Van Duzer said. "A globe you can spin around and bring the part you want to see in front of you."

Eden's rivers

Monte's unique North Pole viewpoint shows a fascinating misconception that some cartographers had at the time. Mainly, he drew the North Pole as four large islands separated by four rivers.

This configuration is seen on other maps and is likely inspired by a now-lost 14th-century book about the claimed fantastic voyage of an English friar who traveled to the North Pole. The friar reported seeing four straits flowing in toward the center of the pole and vanishing down an enormous vortex, Van Duzer said. The friar also claimed that the North Pole had a mountain of magnetic stone, which explained why compass needles pointed north, Van Duzer noted.

The friar's idea was possibly inspired by the Genesis section of the Hebrew Bible, which states, "And a river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it separated and became four heads."

Intriguingly, Monte appears to have applied this conception to the South Pole and multiplied it by two: On the map, the South Pole is broken up into eight islands surrounded by channels, Van Duzer said.

In essence, Monte created parallelism between the poles, Van Duzer said.

The public can see the map at the David Rumsey Map Center at Stanford University or download images of it for free from the center's website.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.