Global Warming vs. Solar Cooling: The Showdown Begins in 2020

The sun may be dimming, temporarily. Don't panic; Earth is not going to freeze over. But will the resulting cooling put a dent in the global warming trend?

A periodic solar event called a "grand minimum" could overtake the sun perhaps as soon as 2020 and lasting through 2070, resulting in diminished magnetism, infrequent sunspot production and less ultraviolet (UV) radiation reaching Earth — all bringing a cooler period to the planet that may span 50 years.

The last grand-minimum event — a disruption of the sun's 11-year cycle of variable sunspot activity — happened in the mid-17th century. Known as the Maunder Minimum, it occurred between 1645 and 1715, during a longer span of time when parts of the world became so cold that the period was called the Little Ice Age, which lasted from about 1300 to 1850.

But it's unlikely that we'll see a return to the extreme cold from centuries ago, researchers reported in a new study. Since the Maunder Minimum, global average temperatures have been on the rise, driven by climate change. Though a new decades-long dip in solar radiation could slow global warming somewhat, it wouldn't be by much, the researchers' simulations demonstrated. And by the end of the incoming cooling period, temperatures would have bounced back from the temporary cooldown. [Sun Storms: Incredible Photos of Solar Flares]

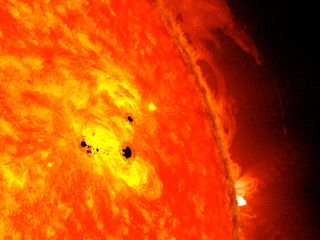

Sunspots, which appear as dark patches on the solar surface, form where the sun's magnetic field is unusually strong, and the number of sunspots waxes and wanes in a cycle that lasts about 11 years, fueled by fluctuations in the sun's magnetic field.

But during the late 17th century, the sun's spots all but disappeared. This episode corresponded with a period of exceptional cold in parts of the world, which scientists have explained as being connected to the changes in solar activity.

Sunspot activity was high in 2014 and has been dipping ever since, as the sun moves toward the low end of its 11-year cycle, known as the solar minimum, NASA reported in June 2017. But a pattern of ever-decreasing sunspots over recent solar cycles resembles patterns from the past that preceded grand-minimum events. This similarity hints that another such event may be fast approaching, the researchers reported in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And the scientists have estimated how intense such an event might be, by analyzing close to 20 years of data recording radiation output from stars that follow cycles similar to that of our sun. Solar radiation output typically drops during a normal solar minimum, though not enough to disrupt climate patterns on Earth. However, UV radiation output during a grand minimum could mean activity plummets by an additional 7 percent, the researchers wrote in the study. As a result, air temperatures on Earth's surface would cool by as much as several tenths of a degree Fahrenheit (a change of a half-degree F is the equivalent to about three-tenths of a degree Celsius) on average, according to the study.

The study's findings will help scientists create more accurate climate model simulations, to improve their understanding of the complex interplay between solar activity and climate on Earth, particularly in a warming world, the study's lead author, Dan Lubin, a research physicist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement.

"We can therefore have a better idea of how changes in solar UV radiation affect climate change," he said.

The findings were published online Dec. 27, 2017, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.