Were Dinosaurs Having a Party Millions of Years Ago in NASA's Backyard?

About 110 million years ago, two tank-like dinosaurs — a baby and an adult — walked across what was a squishy wetland, leaving behind five-fingered handprints in what is now the backyard of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, a new study finds.

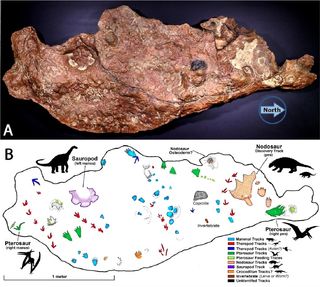

These armored dinosaurs, known as nodosaurs, were in good company. A dinner-table-size sandstone slab that holds their fossilized prints also captured the trackways of other dinosaurs and ancient mammals that lived during the Cretaceous, the last period of the dinosaur age.

"It's a time machine," Ray Stanford, a dinosaur-track expert and amateur paleontologist, said in a statement. "We can look across a few days of activity of these animals, and we can picture it. We see the interaction of how they pass in relation to each other. This enables us to look deeply into ancient times on Earth. It's just tremendously exciting." [In Photos: Baby Stegosaurus Tracks Unearthed]

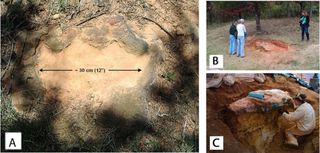

Stanford discovered the stone slab in 2012 while dropping off his wife, Sheila, at work at Goddard. A curious-looking rock outcrop on a hillside behind Sheila's building caught his eye. A closer look revealed a 12-inch-wide (30 centimeters) dinosaur track, and later excavations showed that the 8-by-3-foot (2.4 by 0.9 meters) slab contained about 70 track marks belonging to a medley of eight extinct dinosaur, pterosaur and mammal species.

Warm-blooded party

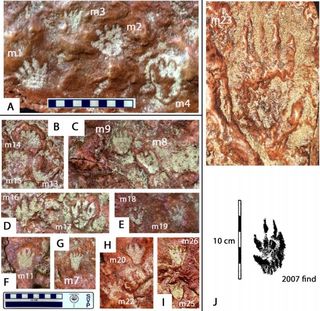

Of the 70 prints, at least 26 belong to squirrel- and raccoon-size mammals, the researchers said. This finding is remarkable, they added, given that it's incredibly rare to find fossilized trackways belonging to dinosaur-age mammals. Until now, there were only four scientifically named mammal trackways from the Mesozoic: one from the Jurassic period and three from the Cretaceous. (Just like with new species, researchers can give scientific names to animal trackways.)

A 4-inch-long (10 cm) track belonging to the raccoon-size mammal is the largest mammal print from the Cretaceous on record. Its size is surprising, given that most dinosaur-age mammals were the size of squirrels or prairie dogs, the researchers said.

Other mammal-made footprints on the stone slab occur in pairs. "It looks as if these squirrel-sized animals paused to sit on their haunches," study co-researcher Martin Lockley, a paleontologist at the University of Colorado Denver, said in a statement. These prints are so distinct, the researchers named them Sederipes goddardensis, which honors the Goddard Space Flight Center.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The concentration of mammal tracks on this site is orders of magnitude higher than any other site in the world," Lockley said. "This is the mother lode of Cretaceous mammal tracks."

Footprints galore

In addition to the baby and adult nodosaur prints, the researchers identified track marks from a long-necked sauropod, small theropods (mostly carnivorous, bipedal dinosaurs related to Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex) and pterosaurs, a group of flying reptiles that includes pterodactyls.

This diversity of tracks suggests that the animals were there to find food, Lockley and Stanford said. Perhaps the mammals were eating worms and grubs, and the small, carnivorous dinosaurs were dining on the mammals, Lockley and Stanford said. The pterosaurs may have targeted both the small dinosaurs and the mammals.

An analysis of the prints indicates that the tracks were likely made within a few days of each other and may even show the footprints of a predator chasing its prey. [Gallery: Reconstructed Dinosaur 'Chase']

"We do not see overlapping tracks — overlapping tracks would occur if multiple tracks were made over a longer period while the sand was wet," study co-researcher Compton Tucker, an Earth scientist at NASA Goddard, said in the statement. "People ask me, 'Why were all these tracks in Maryland?' I reply that Maryland has always been a desirable place to live."

During the Cretaceous, Maryland was hotter and swampier than it is now. "This could be the key to understanding some of the smaller finds from the area, so it brings everything together," Lockley said. "This is the Cretaceous equivalent of the Rosetta stone."

The study was published online yesterday (Jan. 31) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.