How to Watch the Super Blue Blood Moon Lunar Eclipse

A lunar eclipse on Wednesday comes equipped with all sorts of superlatives — and most of North America will get to see at least some of the event.

The "Super Blue Blood Moon" eclipse will occur in the wee hours of the morning on Wednesday, Jan. 31, when the full moon will pass through the Earth's shadow. Viewers on Earth will see the face of the moon turn a murky red.

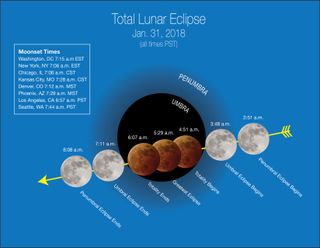

On the West Coast, totality (the full shading of the moon) will occur at 4:51 a.m. PST until 6:08 a.m. PST. Before that, the moon will enter the outer portion of the Earth's shadow, or penumbra, at 2:51 a.m. PST. The real show will become visible starting at 3:48 a.m. PST, when the moon will be entering the umbra, or central portion of Earth's shadow, and a dark shadow will move over the face of the moon. The moon will leave the umbra at 7:11 a.m. PST. [Super Blue Blood Moon 2018: When, Where and How to See It]

Time zone shuffle

East Coasters can catch the partial lunar eclipse before dawn, but they will miss totality because the moon will have set below the horizon by 7:06 a.m. EST. To see the shadow of the Earth become visible on the moon's face, look up at 6:31 a.m. EST; by 6:48 a.m. EST, the moon will be entering the umbra, or central portion of the shadow, which should make the color change more apparent.

For viewers in the Central and Mountain time zones, the moon will set either during the total eclipse or while the satellite is exiting the Earth's shadow. The moon enters the dark umbra at about 5:48 a.m. CST and will hit totality slightly before moonset, at 6:51 a.m. CST. [Stop the Lunacy! 5 Mad Myths About the Moon]

The umbra will appear at 4:48 a.m. MST, and the moon will enter totality at 5:51 a.m. MST. Viewers in the Mountain time zone will also get the chance to see the middle of totality, when the moon is up to 100,000 times fainter than usual, at 6:29 a.m. The eclipse will end slightly before moonset, at 7:07 a.m. MST.

Viewers in Alaska and Hawaii will get a full dose of totality, too, but they'll have to be very early birds or night owls. Totality begins at 3:51 a.m. AKST and ends at 5:05 a.m. AKST. Totality hits at 2:51 a.m. HST and will be over by 4:05 a.m. HST.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blue blood super what?

So why all the extra jargon in front of "lunar eclipse?" Well, "blood moon" simply refers to the brick-red color that the moon turns during a lunar eclipse. That color comes from the light from the sun leaking out around the Earth's disk; essentially, the moon is bathed in the light from Earth's sunrises and sunsets.

The "blue" descriptor doesn't refer to anything skywatchers can actually see; a blue moon is the second of two full moons that occur in the same month. January 2018 first saw a full moon on Jan. 1 or Jan. 2, depending on location.

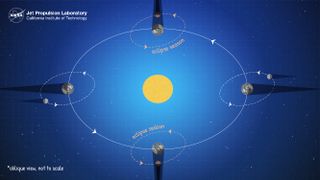

And as for "super," a supermoon occurs when a full moon happens to hit when the moon reaches perigee, the closest point in the natural satellite's orbit to Earth. The difference between perigee and apogee, the farthest point, is around 26,200 miles, or 42,165 kilometers. This translates to a very small difference in brightness and apparent size.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.