The body may have an internal scale that senses how much a person weighs, so the body can regulate fat mass in response, a new study in rodents suggests.

If the findings hold up in humans, the research could pave the way to novel treatments for obesity, researchers said in the new study. The results may also provide an explanation for why sitting leads to weight gain, the researchers said.

"The weight of the body is registered in the lower extremities. If the body weight tends to increase, a signal is sent to the brain to decrease food intake and keep the body weight constant," study co-author John-Olov Jansson, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, said in a statement. [11 Surprising Things That Make Us Gain Weight]

Loaded mice

In the new study, Jansson and colleagues implanted capsules into the abdomens of obese rats and mice. Half of the mice had "heavy" capsules that were equivalent to 15 percent of the animals' bodyweight. The other group had empty capsules implanted into their bellies.

After two weeks, rodents in both groups had roughly the same total body weight, including the implants — meaning the rats with implanted weight capsules had shed roughly 80 percent of the equivalent amount of fat. In necropsies after the experiments, the weight-loaded rats had less white fat than their lighter-bellied counterparts.

To investigate why the loaded rodents were slimming down, the team did a battery of tests and confirmed that the weight-bearing animals did not have more brown fat or increased energy expenditure. Rather, the animals were simply eating less, the researchers reported online Dec. 26 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. To make a comparison, the scientists fed the amount of food that the weighted mice freely ate to another group of (unweighted) mice; these mice lost the same amount of weight, the study found.

The effects were both long-lasting and operated in both directions, the team found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Removal of the loading increased the biological body weight and the fat mass, but not the skeletal muscle mass, demonstrating that the body-weight sensor is functional in both directions," the researchers wrote in their paper.

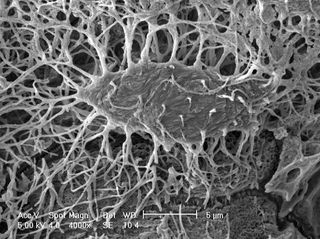

In a battery of other tests, the researchers tried to get at the source of this internal weight sensor. After ruling out a handful of other explanations, from brown fat to appetite-stimulating hormones, the team found that osteocytes, or cells found in weight-bearing bones, seem to be key to the operation of this internal sensor, although they don't yet know exactly how they operate.

Sitting and weight gain

The new findings could provide an explanation for a persistent finding in large-scale studies: People who spend a long time sitting are at increased risk of weight gain, diabetes heart disease and premature death, the researchers said.

"We believe that the internal body scales give an inaccurately low measure when you sit down. As a result, you eat more and gain weight," study co-author Claes Ohlsson, a researcher at the Center for Bone and Arthritis Research at the University of Gothenburg, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular