Dino Family Tree Overturned? Not Quite, But Changes May Lie Ahead

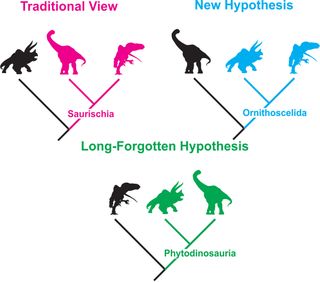

A new dinosaur family tree floated earlier this year isn't quite right, and the old tree, which researchers have accepted as canon for 130 years, isn't much better, a new study finds.

Rather, the two trees, as well as a third tree that researchers have rarely considered, are equally plausible, based on a meticulous anatomical study of dinosaur remains, the researchers said.

"We found that, statistically speaking, all three of these [family tree] hypotheses are indistinguishable from each other," said study co-researcher Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. That means "we're in a period of uncertainty, and that is maybe a little bit unsettling, but it's also fun. There's a huge, fundamental question about dinosaurs that we're going to have to figure out," Brusatte told Live Science. [Photos: Oldest Known Horned Dinosaur in North America]

Unexpected study

This past March, paleontologists worldwide were taken by surprise when Matthew Baron, a doctoral student of paleontology at the University of Cambridge in England, and his colleagues published a study in the journal Nature that redefined how the major dinosaur groups were related to one another.

Traditionally, researchers divided dinosaurs into two main groups: the bird-hipped ornithischian dinosaurs (including duck-billed dinosaurs and Stegosaurus) and the lizard-hipped saurischians, a group that includes theropods (such as Tyrannosaurus rex) and sauropods (long-necked herbivores such as Argentinosaurus).

However, Baron had doubts about the tree. He noticed that even though ornithischians had bird-like hips and theropods had lizard-like hips, the two groups had many similar anatomical features. So, Baron undertook a titanic task: he examined 457 anatomical characteristics in 74 dinosaur species — looking at some in person and reading about others in studies. His results revealed that theropods and ornithischians were closely related, and fit into a previously unknown group called Ornithoscelida.

The findings also suggested that dinosaurs arose in northern Pangea, on what later became the supercontinent Laurasia, rather than an area in southern Pangea that eventually became South America.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rapid response

The Nature study set the world of dinosaur research abuzz, but some researchers were skeptical after noticing problems with the analyses, Brusatte said. Within days of the study's publication, a group of nine international paleontologists decided to double-check the work.

"We thought, 'let's do what scientists are supposed to do and see if this result holds up to scrutiny,'" Brusatte said.

Many of the new study's researchers are early-dinosaur experts who have examined and held the fossilized bones in question. It's a tough field, as early dinosaurs were remarkably similar, and many bones from the Triassic period are broken and deformed, said Andrew Farke, the curator and director of research and collections at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont, California, who was not involved in the new research.

"You take your early dinosaur from any group, whether it's a theropod, a sauropod or an ornithischian, and they are all basically interchangeable," Farke told Live Science. "It's the little details that really distinguish them."

Because of these similarities, it's key that researchers studying early dinosaur relationships examine the bones in person, said Mark Norell, the chairman of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who was also not involved in the study. [In Photos: Wacky Fossil Animals from Jurassic China]

The new group "knows the anatomy better than anybody," Norell told Live Science. "I'm not criticizing the first group who did it — they gave it a try. But at the same time, if you're going to make a provocative statement, you should see more specimens."

Which tree?

The original group made some mistakes while characterizing the fossils, and "we corrected those things and re-ran the analysis," in addition to adding more dinosaur species to the dataset, Brusatte said.

The results showed that the traditional family tree was the best fit, but — surprisingly — it wasn't statistically significant from the tree discovered by Baron and his colleagues. Nor was it statistically different from yet another tree that also reshuffled the relationships. In addition, their statistical analysis indicated that dinosaurs likely originated in southern Pangea, rather than northern.

"What this whole process has revealed is that Baron [and his colleagues] were certainly onto something," Brusatte said. "Their hypothesis is certainly very plausible, but it's not quite time to rewrite the textbooks."

Study lead researcher Max Langer, a paleontologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, agreed.

"Exceptional claims require exceptional evidence," Langer told Live Science in an email. "It is not to say that the hypothesis of Baron [and colleagues] cannot be correct. It can, everything in science can change. But the burden of proof is theirs, and we have shown that the evidence they were putting forward in support of their model was not as strong as necessary to overthrown decades of studies pointing to another direction."

However, Baron is standing by his tree. "I don't think they've come close to disproving the idea," Baron told Live Science. "Their results are not significantly different from our own."

Baron said he disagrees with some of the fossil characterizations that were changed, and said he would prefer the group explain these changes and include him and his colleagues going forward. "I think that's the next step, a large collaborative effort," Baron said. "We should hopefully be able to arrive at a consensus. We are all trying to get the same answer."

There certainly is a lot of work ahead. "It's round two in what's sure to be a pretty long conversation on dinosaur origins and classification," Farke said. "I don't think by a long shot that this will be the last word on it."

The best way forward is to continue studying fossils of early dinosaurs, "ideally those of new species and more complete specimens of existing species," said Matthew Lamanna, the assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who was not involved with either study. "That’s the best way to settle the question of the evolutionary relationships of the major dinosaur groups — Ornithischia, Sauropodomorpha and Theropoda — once and for all." [Photos: Dinosaur's Battle Wounds Preserved in Tyrannosaur Skull]

Once this question is settled, it can help researchers understand how dinosaurs diversified, evolved and took over the world so quickly, said Sterling Nesbitt, an assistant professor of geology at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, who was not involved in either study.

The new study, as well as a rebuttal from Baron and his colleagues, was published online today (Nov. 1) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular