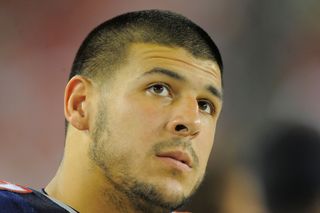

Aaron Hernandez's 'Severe' CTE: How Does It Progress So Quickly?

Former NFL player Aaron Hernandez had one of the most severe cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) ever seen in someone his age, according to his lawyer. But how did his condition progress so quickly?

Hernandez was just 27 when he died from suicide earlier this year. A recent analysis of his brain by researchers at Boston University's CTE Center showed that Hernandez had "stage 3 out of 4" CTE, with stage 4 being the most severe. This is particularly extreme for someone his age — his brain showed the type of damage that is typically seen in pro-football players in their 60s, according to The New York Times.

CTE is a degenerative brain disease found in people with a history of repeated blows to the head, including pro-football players and boxers, according to the CTE Center. It is thought that these repeated hits cause damage to brain tissue, leading to a buildup of an abnormal protein called tau. Currently, the condition can be diagnosed only by examining a person's brain tissue after death. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

The characteristic brain changes of CTE can begin months, years or decades after the last head injury or the end of a person's athletic career, the CTE Center said.

However, many questions about CTE remain, including exactly which factors affect a person's risk of developing CTE or how the disease will progress. Many factors could be involved, but much more research is needed to identify these factors and examine their role in the condition, according to experts. For example, although researchers hypothesize that frequent head trauma plays a role in the disease, it's not clear exactly how many hits to the head a person needs to experience, or how severe the hits need to be, to trigger the brain changes seen in CTE, according to the CTE Center.

Kevin Bieniek, a research fellow in neuropathology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Jacksonville, Florida, said that there may be both genetic and environmental factors that play a role in the risk of developing CTE, and in the disease's progression. Some of these factors might be protective, while others could contribute to a person's risk, he noted.

For example, it's thought that a gene called APOE may influence CTE risk. Some studies have found that a version of this gene, called APOE e4, is more common in people with CTE, compared with people without the disease, suggesting it may be a risk factor for developing the disease, according to a 2011 paper published in the journal Clinics in Sports Medicine. About 57 percent of people with confirmed CTE have at least one copy of the APOE e4 gene variant in their genome (out of the two copies that are inherited from each parent), according to the paper. However, only about 28 percent of people in the general population have at least one copy of the APOE e4 gene, the paper noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The evidence linking CTE with APOE e4, however, is still not conclusive, Bieniek told Live Science, so more studies are needed to confirm that it is a real risk factor.

In addition, a slew of environmental factors could potentially play a role in the disease, such as the number of head injuries a person experiences, the severity of these injuries, and the age at which a person experiences the head injuries, Bieniek said. In addition, a person's use of substances such as alcohol and tobacco might also play a role in the likelihood of developing CTE, he said.

The type of sport a person plays, or even their position (such as a football wide receiver versus a lineman), might also affect a person's risk of CTE, according to the Clinics in Sports Medicine paper.

To better understand how these environmental factors affect a person's risk of CTE, researchers will need to study many cases of CTE and compare them with athletes who don't have CTE, as well as to nonathletes without CTE, Bieniek said. Researchers would also need a lot of information about each of these cases, including their experience with head injuries, and whether they had any psychiatric or neurological conditions.

Ideally, researchers would start studying athletes and nonathletes at a young age, Bieniek said. They would collect information on numerous factors, such as the type of sports and activities they participate in; the number of games they play; the number of concussions or injuries they experience, and how severe these injuries are; and whether they develop symptoms such as memory loss or depression, Bieniek said. Then, after the participants' death, researchers would study the brains for CTE and look for relationships between the studied environmental factors and the risk of CTE.

This "ideal" study would be technically challenging and take a tremendous effort. Currently, "we are trying to answer elements of these questions on select [groups] and populations, and the cumulative findings of these studies will help paint a better picture" of CTE's risk factors, Bieniek said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.