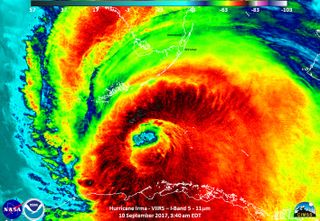

Hurricane Irma: How Good Were the Forecasts?

Hurricane Irma wasn't an easy hurricane to forecast.

The storm's northward turn sent it on a collision course with Florida, and the timing of that turn was crucial to figuring out who would get the worst impacts and what preparations communities across the state should take. And while predictions weren't flawless, experts say the remarkable accuracy of even those imperfect forecasts shows how far hurricane prediction has come from the times when storms would hit without warning and cause hundreds, or even thousands of deaths.

There is still room for improvement, though, and that is where the much-hyped competition between the so-called European and American models comes in, highlighting the need for more sustained investment, according to researchers. [Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm]

Irma also highlights the risks of communicating a constantly evolving forecast, particularly in today's cluttered social media environment, researchers said.

"Quite remarkable" forecast

The forecasts were clear more than a week out that Irma could impact a major population center, "which is a very long lead time," said Chris Davis, head of the Mesoscale & Microscale Meteorology Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. "The very long-range predictions were quite remarkable."

Before the advent of satellites, storms devastated places like Galveston, Texas, and the Florida Keys with no warning. The improvements in forecast models and increases in computer power have substantially improved forecasts from where they were even 20 years ago, as today's seven-day forecasts are about as accurate as a five-day forecast was back then, Davis and others said.

But as Irma came closer to Florida, it was still difficult to pin down where landfall would occur and even which coast the storm would hit.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The trick, as it usually is, is predicting where exactly this thing is going to hit," Davis told Live Science.

Initially, forecasts predicted that Irma would rake up Florida’s east coast, but as the storm hit Cuba, the models' predictions shifted to the west. But "there really was a pretty wide spread of tracks" from the models, Davis said, even for the vaunted European model.

While models can, and should, be further improved, there's a limit to just how exact they'll be able to get, because the atmosphere "does have an intrinsic limit of predictability," Davis said. That limit is generally thought to be 14 to 18 days because of the naturally chaotic state of the atmosphere, Shawn Milrad, an assistant professor of meteorology at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida, told Live Science.

"I think we have to be really careful about our expectations before these events," Milrad said. Expecting models to pinpoint landfall within 20 to 30 miles (32 to 48 kilometers) about five days out "is really something we shouldn't be doing," he said. [Hurricane Irma by the Numbers]

Euro vs. GFS

Global weather models are good at representing the large-scale patterns in the atmosphere that steer hurricanes, but those models simply aren't fine-tuned enough to capture what's going on inside hurricanes, and this impacts their forecast ability, said Ryan Maue, a research meteorologist and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute.

Additionally, some processes — such as the friction that occurs when a hurricane encounters land, like Irma did with Cuba and Florida ¾ are governed by equations too complex to put straight in the models Milrad said. So, these factors must be approximated, which introduces uncertainty, he said.

Improving forecasts will require a combination of factors: more and better observations to feed into models, more computer power to run the models, a better representation of the physical processes of the atmosphere in the models and, most crucially, Davis said, better methods to ingest the observations into models.

This is where the European model, run by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) particularly excels over the Global Forecast System model, one of the models run by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Davis and others said. "And they spend a lot of effort in that particular area," which is why that model is overall more skillful than the GFS, Davis said of the ECMWF. (The Euro had its imperfect moments, though, as it predicted Irma would continue up along the west coast of Florida, instead of making landfall around Naples as it actually did, Milrad said.)

However, "the GFS is not a crappy model; it's a good model. It's much better than it was five years ago, when it blew Sandy," Maue said, referring to the model missing the turn toward the Northeast that Hurricane Sandy made in 2012, which the Euro caught.

But while the output of the two models can be compared, it is hard to compare their parent organizations. The ECMWF is supported by 34 member nations and works solely on medium-range weather forecasts, done using its one model. That organization also has a research team dedicated to constantly improving the model. The modeling arm of NOAA, on the other hand, maintains numerous models and is subject to the year-to-year funding decisions of the U.S. Congress, Maue and others said.

NOAA is moving toward streamlining its modeling effort, but that will take sustained investment, Davis and others said. While events like Hurricane Sandy can mean more attention from Congress and more funding, that attention eventually wanes, David said. In general, funding is kept level from year to year.

"It really hampers what we can do. It just takes longer to do things," Davis said.

Social media: "Blessing and a curse"

The forecasts and models alone don't tell the full story of how information about hurricane risk reaches the public. The communication of that forecast is also critical to making sure communities know what is coming and what they need to do to prepare.

In the age of social media, people have access to so much more information, which can be good, but this can also add challenges, said Gina Eosco, a social scientist with Cherokee Nation Company working in support of NOAA. "That's a blessing and a curse," she said.

For example, when the forecast was trending toward a landfall in eastern Florida, some residents decamped for Tampa or Naples, only to find themselves in harm's way when the forecast shifted. This happened despite efforts to underscore that Irma was a risk to the whole coastline and that the exact track was uncertain.

The perennial problems of communicating hurricane risk are compounded in the social media era, because tweets or Facebook posts that are hours or even days old surface in feeds and cause confusion, Eosco said. That's not even mentioning the sheer amount of information now available, which can be overwhelming and make it hard for people to find what's most relevant for them, Eosco said. During Irma, for example, someone in Miami would have needed different information than someone in Naples.

Additionally, some people who aren't trained meteorologists might post a single iteration of one model and sow panic and confusion because of what it shows, Milrad said. But meteorologists never rely on a single model run or even a single model.

"That is the conundrum of having that information out there without the human forecaster interpretation," Eosco said. Forecasters "know all the strengths, the weaknesses, the biases" of the different models.

And even when meteorologists post so-called model "spaghetti plots," which show the range of predictions from a model, these experts need to be careful to add context,.

"Explaining the 'why?' and the 'what's behind this?' has been lost, I think," Milrad said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.