Photos: Teeth Show Humans Arrived in Southeast Asia Up to 73,000 Years Ago

Curious fossils

An international team of researchers has reevaluated early human fossils found in the Lida Ajer cave, on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, to show that anatomically modern humans were present in Southeast Asia around 20,000 years earlier than scientists previously thought.

The research establishes that modern humans were present at the cave, in the highland rainforests of the west of Sumatra, between 63,000 and 73,000 years ago. [Read more about the ancient teeth found in Indonesia]

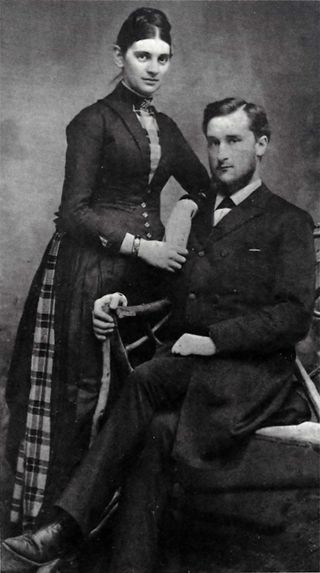

Pioneering paleontologist

The latest study is based on the findings of the pioneering Dutch paleontologist Eugene Dubois, who traveled to Sumatra with his wife Marie in the late 1880s to excavate several caves.

Dubois was a devotee of the theories of Charles Darwin, and he hoped to find fossils that would establish an evolutionary "missing link" between humans and apes.

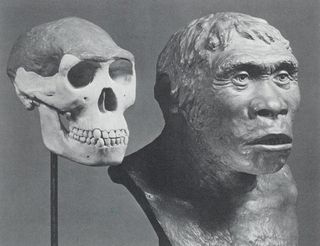

Java Man

Dubois' most celebrated discovery was the fossilized bones of an early human that he excavated from a cave on the Indonesian island of Java in 1891 and 1892.

Dubois thought the remains were probably from an "aged female," but the specimen became known as "Java Man."

Paleoanthropologists today recognize Java Man as a member of the early human species Homo erectus erectus, which lived around 1 million years ago.

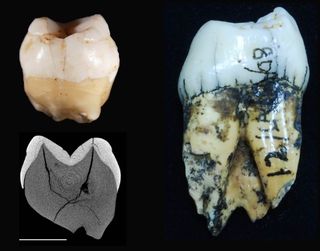

Ancient teeth

The latest research focuses on two ancient teeth that were discovered in a breccia rock deposit in the Lida Ajer cave by Dubois sometime in the late 1880s.

The teeth are kept at the Museum Naturalis at Leiden in the Netherlands, which maintains a collection of Dubois' fossil finds and other research. Although the teeth were confirmed as human in the 1940s, the lack of a firm chronology for the rock deposits in the Lida Ajer cave where they were found meant that their significance remained uncertain.

Returning to the site

In 2008, Australian geochronologist Kira Westaway traveled to Sumatra to relocate the Lida Ajer cave where Dubois found the teeth. She spent a week exploring caves in the heavily forested highland area with local guides before finding the right one.

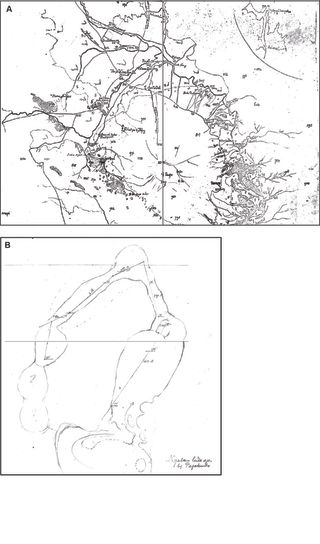

"X" marks the spot?

Westaway was able to confirm she had found the right cave thanks to a map and description of the cave's interior recorded by Dubois in his field notebooks, which are part of the collection at the Museum Naturalis in Leiden in the Netherlands.

Confirming chronology

In September 2015, paleontologists Gilbert Price, of the University of Queensland, and Julien Louys, of the Australian National University, returned to the Lida Ajer cave. They wanted to establish a firm chronology for the teeth found by Dubois more than 120 years earlier.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Barricades to overcome

Access to the Lida Ajer cave proved difficult at first, when the researchers found that local people had placed a locked gate over the cave entrance to protect flocks of swallows that build their nests in crevices in the limestone.

The nests are a key ingredient of Birds Nest Soup, a Southeast Asian delicacy.

Finding history

Eventually, the researchers were able to gain access to the cave's interior to document in detail the deposits where Dubois found the teeth in the 1880s. The scientists also took samples of the rock and fossilized animal remains from the deposit that would undergo sophisticated dating tests back in Australia.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.