How Hurricane Irma's Winds (Temporarily) Drained Tampa Bay

Hurricane Irma's strong winds didn't just whip around palm trees, knock down power lines and rip off roofs — they also pushed aside vast amounts of shallow water, temporarily leaving behind a bare seabed along the coast of Tampa Bay, according to a video taken Sunday (Sept. 10).

As Irma moved toward Florida, Twitter user @scheuster let his dogs gallop around an empty (or, at least, waterless) Tampa Bay. He posted, "#Tampa bay now an effective dog park as we wait for #irma. With @CityofTampa parks closed ahead of storm, this is the best we've got."

Parts of the bay were empty because the hurricane had blown away the water, akin to pointing a leaf blower toward a puddle and pressing the "on" switch, said Gary Lackmann, a professor in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at North Carolina State University. "The wind is going to push the water away," Lackmann told Live Science. [Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm]

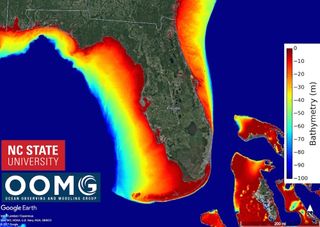

It's not uncommon for tropical storm winds to displace shallow water, but Irma's effects were stark in Tampa Bay, which has a gradually sloping ocean floor on the West Florida Continental Shelf, said Joseph Zambon, a research assistant professor in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at North Carolina State University.

"The gentle slope means that a change in sea level of a few meters would result in hundreds of meters of expanded beach," Zambon told Live Science in an email. "If the storm were to have transited along the east coast of Florida near the Florida Strait, this impact would have been much less pronounced, as the shelf quickly falls off east of Miami."

As Tampa Bay's waters were blown offshore, pushed by the strong westward winds on the northern side of Hurricane Irma, the water piled up toward the Gulf of Mexico. But the impact of this extra water was "negligible" — just a drop in the bucket compared with the vast Gulf, Zambon said.

A similar occurrence happened in Long Island Bahamas, with Twitter user @Kaydi_K recording the ocean floor sans water. "I am in disbelief right now... This is Long Island, Bahamas and the ocean water is missing!!!" she posted on Saturday (Sept. 9).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This loss of water can also be caused by the low pressure in the hurricane's eye, the center of the hurricane, Lackmann said. This low pressure can cause a "bulge" of raised water in the eye, and that extra water comes from outside of the eye, he said.

Safety first

It can be tempting to walk out on the new exposed seafloor, but experts discouraged it. As the hurricane's eye passes, its winds will shift and "push the coastal water and additional surge back toward the coast in a matter of minutes," Zambon said. "The dramatic impact of the water receding caused by the gradual seafloor sloping will be even more dramatic as the water returns and additional surge approaches."

If people are caught in the surf, they'll have to fight off surface currents, rips and waves, "and you can be quickly swept out to sea," Zambon warned.

This is exactly what happened when an infamous hurricane hit Galveston, Texas, in 1900, said Frank Marks, the science lead for the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

However, there was little hurricane forecasting back in those days, so the people of Galveston had no idea they were in the path of a Category 4 hurricane that was poised to kill about 8,000 people. [The 20 Costliest, Most Destructive Hurricanes to Hit the US]

"As the hurricane approached, the wind was such that it drove the water out of Galveston Bay," Marks told Live Science. "People were surprised by that because, again, they didn't know a hurricane was coming. They walked out onto the tidal flats and the water came back … a lot of people drowned because they weren't expecting that."

Depending on the geography of the seafloor and meteorological factors, water can refill within minutes to a few hours.

"We are already seeing the water returning [in Tampa Bay]," Zambon said on Monday (Sept. 11). "After reaching a low around 9:30 p.m. EDT [Sunday], the water levels have already increased by about 1.5 m [5 feet] through 7:30 a.m. EDT [Monday]."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.