How Hurricane Irma Could Change Florida's Coast

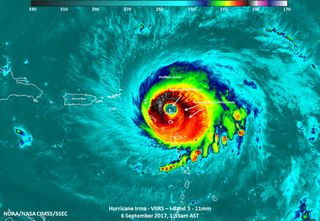

As Hurricane Irma ravages the Caribbean, Florida is bracing for potential landfall. The huge storm, currently a Category 5 with maximum sustained winds of near 180 mph (290 km/h), is expected to rake the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Bahamas and parts of Cuba before turning north toward the U.S. mainland this weekend.

It's too early yet to forecast precisely where Irma will hit or how strong it will be when it does, but the National Hurricane Center's forecast cone, which shows the potential paths for the storm's center, envelops all of the Florida Panhandle. If the storm does hit as a Category 4 or 5, the impacts on at least some part of the coast may depend on the only thing between water and infrastructure: sand dunes.

"We often refer to the sand dunes along the coast as the first line of defense," said Joseph Long, a research oceanographer with the U.S. Geological Survey in St. Petersburg, Florida. Long and his colleagues are using National Hurricane Center data to predict which dunes will hold back the sea — and which won't — depending on where Irma strikes. [Hurricane Irma: Everything You Need to Know About This Monster Storm]

Natural barriers

Sand dunes are serious business for coastal communities. In his request to the federal government for an emergency declaration for all of Florida, the state's governor, Rick Scott, wrote that many of the state's dunes were compromised by 2016's Hurricane Matthew, which strafed the east side of the state as a Category 3 storm. Dunes can protect roads and buildings from storm surge and waves. The quality of this protection depends on the size and height of the dunes, as well as the length of the storm and how continuous the dune field is, said Ping Wang, a coastal geologist at the University of South Florida.

"There are places where there are high dunes, and there are lower dunes," Wang told Live Science. "The high dunes survive, [but] the water can still get behind and erode away the lower dunes."

The water can also travel around dunes, Wang said. A high dune might protect a beachside home from pounding waves, but if that dune isn't very long, the house could still flood.

There are three ways that dunes fail in storms, according to Long. The first is dune erosion, in which water rises up to the face of the dune and nips at it, pulling the sand offshore and narrowing the dune. The second is overwash, which means that the combination of the storm surge, tides and waves overlap the dune. Overwash pushes sand from the top of the dune landward, Long said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Finally, there's inundation, which means that the storm surge and tides alone are enough to put the entire dune underwater. Hurricane Matthew, which Scott cited in his request for emergency help, mostly affected dunes by erosion, Long said. He and his colleagues took aerial photos after that storm and found that Matthew caused overwash of about 11 percent of the dunes on Florida's eastern shores. (The outcome was more serious in Georgia and South Carolina, where the storm overwashed 30 percent and 58 percent of dunes, respectively.)

Preparing for Irma

In terms of Irma's expected impact on dunes, the storm looks less like the relatively small and quick-moving Matthew and more like Hurricane Ivan, Wang said. Ivan, a 2004 storm that reached Category 5 strength in the Caribbean, hit Florida as a strong Category 3. [Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm]

"Ivan took out a lot of dunes and it took a very long time for the dunes to recover," Wang said. That meant extra damage in the 2005 hurricane season, he said, when Hurricane Dennis made landfall in the same area.

"If the dune is gone, the next storm could cause trouble," Wang said.

In preparation for Irma, Long and his colleagues at the USGS are issuing predictions for overwash, erosion and inundation of dunes at the Coastal Hazards website. The predictions take into account the tides, storm surge and waves predicted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and add in the USGS' wave run-up predictions, which estimate how high up any given beach the waves will reach, Long said. Another tool, the Total Water Level and Coastal Change Forecast, aims to predict when and where the water level will increase.

There's still a lot of uncertainty in these predictions, Long said, because the storm's track is still unknown. In general, he said, the dunes on the eastern coast of Florida are a bit higher, and thus more resilient, than the Gulf Coast dunes, but that doesn't mean that eastern Florida is a safe place to be. And, of course, the storm surge and waves are only part of the danger — Irma's winds and heavy rains are their own destructive force.

Regardless of precisely where the storm hits, Long said, any impact on Florida is likely to include overwashed and altered dunes.

"There's no doubt that you can expect the coast to look dramatically different after a storm like Irma passes," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular