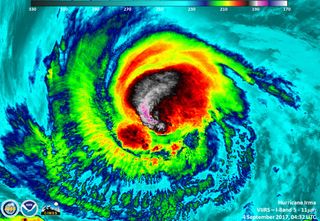

Why Category 5 Hurricanes Like Irma Are So Rare

Hurricane Irma has become one of the strongest Atlantic hurricanes in recorded history; the Category 5 storm's monstrous winds are currently whipping at 185 mph (298 km/h) near its core as it barrels toward the Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico and possibly Florida.

Only four other Atlantic storms have been known to achieve such strength, according to Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane expert at Colorado State University: an unnamed Labor Day storm, in 1935; Allen, in 1980; Gilbert, in 1988; and Wilma in 2005.

The list of such storms is small because, to reach such stupefying intensity, "everything about the environment needs to be perfect," said Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami. [Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm]

For a storm to become as strong as Irma, he said, it needs a deep pool of warm ocean waters to fuel the convection at its core — "basically no vertical wind shear," or winds that change direction and speed with height and can inhibit storm development; and distance from land, as the friction the winds experience as they blow over land can weaken the storm.

All of these things have come together with Irma. "It's got absolutely everything working in its favor for it right now," McNoldy told Live Science.

Ingredients for a monster storm

The unlikeliness of all those conditions being in place when a storm system is also present is why there are only 35 known Category 5 hurricanes on record in the Atlantic, going back to the early 20th century, according to Mark Bove, a meteorologist with Munich Re, a reinsurance company. The first was an unnamed hurricane that hit Cuba in 1924.

Storms this strong are not quite as rare in the northwest Pacific because of the larger area of warm, open ocean that they can draw from, McNoldy said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The strongest winds on record for an Atlantic hurricane were the 190-mph (306 km/h) winds of Allen in 1980, according to Klotzbach. It’s possible Irma could meet or top that record, he told Live Science in an email. The most recent Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic basin was Matthew, last year. But Matthew was the first Category 5 storm in the basin since Hurricanes Dean and Felix in 2007, showing how long the region can go without seeing such a storm.

"From year to year, the ocean and the atmosphere aren't always going to be able to allow everything to happen," McNoldy said.

It is even rarer for a hurricane to make landfall as a Category 5 storm, as Matthew, which weakened before landfall, shows. The last Category 5 storm to hit the U.S. was Andrew, in 1992, which flattened parts of South Florida.

Andrew was a small storm that intensified quickly and had very warm waters off the east coast of Florida to draw from, helping it to overcome the interaction with land that would normally weaken a storm, McNoldy said. [A History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

Nature's biggest storms

The only other Category 5 hurricanes to hit the U.S. since the beginning of the 20th century were the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, which raked the Florida Keys, and Hurricane Camille, which hit Mississippi and Louisiana in 1969.

Category 5 storms don't typically stay at that strength for extended periods of time, McNoldy said. Intense hurricanes undergo a process called an eyewall replacement cycle that happens as the eyewall — the circle of the strongest winds around the central eye of the storm — contracts. Eventually, a new eyewall forms on the outside of it and chokes off the old eyewall. As that process happens over the course of about 18 to 24 hours, the storm usually dips in strength, but it can strengthen again once the process is complete.

There's no immediate sign that an eyewall replacement cycle is happening anytime soon with Irma, McNoldy said, but forecasters will be watching for it as hurricane hunters fly in and out of Irma and satellites keep a close watch on its development.

Irma will first hit the Leeward Islands as a Category 5 storm before impacting Puerto Rico, though how close a blow the U.S. territory will get is still uncertain. A key question is when Irma will make an expected turn to the north, which will affect which parts of Florida it might impact and how strong it might be when it does so. Right now, the Florida Keys seem the most likely to be impacted; county officials have already issued a mandatory evacuation order for visitors beginning Wednesday morning. Florida's governor has also declared a state of emergency in response to Irma.

The forecast from the National Hurricane Center for five days out — about the time it would take the storm to reach Florida — still has Irma as a major hurricane. Forecasts are typically too uncertain that far out to say whether Irma might still be a Category 5 storm if and when it reaches Florida, but "a 5 is certainly within the realm of reality," McNoldy said.

If Irma continues on its current west-northwest track, it could interact enough with Hispaniola (the island that includes the Dominican Republic and Haiti) and Cuba for the storm to weaken before it reaches Florida (though this would mean bigger impacts for those islands), he said.

Category 4 and 5 storms are expected to become more common in the future because of the impacts of climate change. While scientists think the number of storms overall may decrease, the strongest storms will make up a higher proportion of those that do occur because of warmer ocean waters.

"In the long-term trend, if you warm the oceans, it just makes it a little more likely to be able to sustain a stronger storm," McNoldy said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.