Medieval Farmers May Have Skinned Cats for Pagan Rituals

Farmers skinned cats about 1,000 years ago in Spain, possibly for the medieval cat-fur industry or a "magical" pagan ritual, a new study finds.

Scientists found evidence of the skinning at the archaeological site of El Bordellet in eastern Spain, where medieval artifacts were discovered during highway construction in 2010.

During more recent excavations, researchers found nine pits that likely held crops from medieval farms. A number of these pits held bones from sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, dogs and horses.

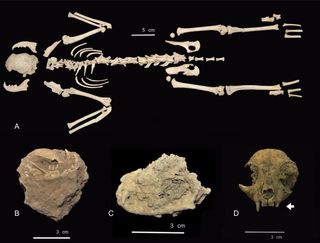

One pit was notable because it contained an unusual amount of feline remains — about 900 domestic cat bones. One such bone was carbon dated to about A.D. 970 to 1025. [See Photos of the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Kittens]

Skinned cats

Several clues led the archaeologists to conclude that the cats were likely skinned. The number, angle, intensity and location of the cut marks and fractures seen on the bones were consistent with those seen in prior experiments where researchers skinned a variety of animals.

The state of the bones suggests that most of the felines were 9 to 20 months old when they died. The researchers said this age was likely the best for cat-fur usage, when the felines were relatively large but their fur was still free of damage, parasites or disease.

Cat skinning has been seen widely at numerous archaeological sites in northern Europe, especially Britain and Ireland, the researchers said. "The skins were basically used for making garments, mainly coats," as well as collars and sleeves, said study lead author Lluís Lloveras, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Barcelona. "Some texts also make reference to the healing qualities of cat skin, but also to its possible harmfulness."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cat fur was often traded during the Middle Ages, according to archaeological finds and medieval texts, Lloveras said. "The skins of the cat and the rabbit have many similarities in terms of quality and touch," Lloveras told Live Science.

Both domestic cats and wildcats were skinned for the fur industry, although the value of domestic-cat fur "could be worth 100 times less than that of the wildcat," Lloveras said. "The fur of domestic cats was normally used by less-wealthy people or social groups that had to demonstrate a certain austerity, like nuns."

A 2013 study in the journal Antiqvitas found evidence of cat skinning in the Muslim areas of medieval Iberia. This new study may be the first conclusive evidence of cat-fur usage in the medieval Christian parts of Iberia, the European peninsula containing Spain and Portugal. "This proves that cat-fur exploitation was common in both [the] Christian and [the] Muslim world," Lloveras said.

Pagan cat rituals?

However, the researchers said there might be another explanation for this cat skinning: a magical pagan rite. Other animal remains uncovered alongside the feline bones included a whole horse skull, a goat horn fragment and a chicken eggshell.

"All these particular animal remains have been associated with ritual practices in the Middle Ages as well as in later times," Lloveras said. For instance, a 1999 study in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology found a partial cat skeleton buried with several hens underneath a wall from the late-15th to early-16th centuries in England, perhaps as part of a commemorative ritual during construction, he said.

However, the researchers cautioned that the archaeological record in this region does not make it clear whether these bones were placed together coincidentally or as part of a ritual. "We will wait for new future discoveries in the area," Lloveras said.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 24 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular