California Prepares for Solar Power Loss During the Great Eclipse

A total solar eclipse that will sweep across the United States on Aug. 21 is expected to make a noticeable dent in solar-energy collection, prompting energy workers to concoct workarounds that will help them meet energy demands while the eclipse passes overhead.

Utility workers already have a game plan in California, where 9 percent of electricity came from utility-scale solar plants in 2016. During the eclipse, when the sun disappears behind the moon, power grid workers plan to ramp up energy output from other sources, including from hydroelectricity and natural gas, and then quickly reintroduce solar power as the sun reappears.

In all, California's residents shouldn't notice a difference in their power supply during the duration of the eclipse, said Steven Greenlee, a spokesman for California Independent System Operator (ISO), a nonprofit that manages California's power grid. [Sun Shots: Amazing Eclipse Images]

Even though the eclipse isn't passing directly over California — it's traveling in a curved path from Oregon to South Carolina — it will still affect the Golden State, which has nearly half of the nation's solar-electricity-generating capacity, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

"The solar eclipse is farther north of us, but we will see between 50 [percent] and 75 percent of solar production from our solar plants reduced during that [time]" Greenlee told Live Science.

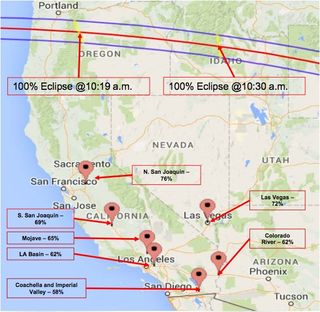

The state is expected to lose almost 4,200 megawatts during the eclipse, which will partially darken the state from about 7:45 a.m. to 12:45 p.m. local time, with peak occlusion happening from 10:19 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. local time on Aug. 21, according to the ISO. To put that in perspective, 1 megawatt powers about 1,000 typical homes, so the eclipse could affect the equivalent of about 4.2 million homes, Greenlee said.

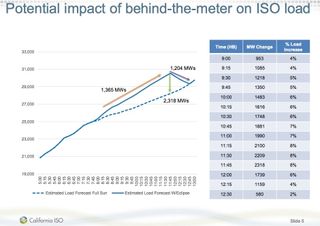

In addition, units that rely on power from rooftop solar panels will go offline, "which means that those mostly residential units will then look to the grid for their power support," Greenlee said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When these units are added to the expected loss of 4,200 megawatts, the total estimated demand on the power grid will be about 6,000 megawatts, or the equivalent of about 6 million homes, according to the ISO. (California had a population of about 39.2 million people in 2016, according to the U.S. Census.)

"[The 6,000 megawatts] is the amount of megawatts that we expect that we'll have to generate to make up for the effect of the solar ellipse," Greenlee said. "For us here at the ISO, we're going to need to make sure that we have our reserves properly procured," which involves having 100 percent of the expected demand plus an additional 6 percent in reserves, just in case, he said.

The ISO is talking with other energy providers, particularly natural gas, which provides about 53 percent of California's energy resources, Greenlee said. This way, the generators will know that they'll need to acquire more natural gas for the morning of the eclipse.

In addition, the ISO will have to properly time the fading out and sudden return of the sun's light. As the eclipse begins passing over California, solar-energy collection will decrease at 70 megawatts per minute until the sun is fully blocked by the moon. Then, as the eclipse ends, it will return at 90 megawatts per minute, which is "very fast," Greenlee said.

"The challenge on our end is going to be able to time bringing up the resources, the natural gas or the hydro-generation that we're going to need, as the solar is ramping down," he said. "And then, we're going to have to ramp the gas and hydro-generation down as the solar is ramping up."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular