Weird Ants Have Hairy Blobs for Babies

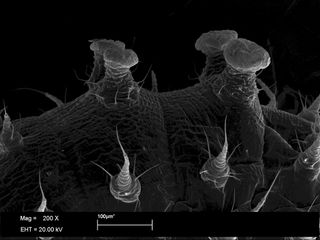

These are not bouncing bundles of joy — the babies of trap-jaw ants are studded with spines, spires and fleshy "doorknob" protuberances.

New research zooms in on these bizarre larvae in more detail than ever before. Scientists used scanning electron microscopy to describe the larval development of trap-jaw ants, a group of carnivorous ants known for its hair-trigger mandibles that deliver a nasty bite.

It's the first time anyone has described the development of these ants, and a rare type of study in the field of ant research. Only 0.4 percent of the 16,000 known species of ants have had their larval stages studied. [Bizarre Babies: A Gallery of Trap-Jaw-Ant Development]

Snappy ants

Trap-jaw ants are in the genus Odontomachus, a group of ants defined by their large mandibles, or jaws. The jaws are locked open until something triggers the sensory hairs on them. Then, they snap shut like Venus flytraps. The jaws can move at a speed of 210 feet per second (64 meters per second), according to 2006 research. The ants sometimes use their jaws as a springboard to propel themselves upward.

The ants' larvae are far less mobile. They look like bulbous blobs covered in spiky hairs, and they hang out in the ants' underground nests, literally suspended by little knobs on their backs from the ceiling and walls.

A team of researchers led by Daniel Solis, who studies social insects at São Paulo State University in Brazil, used scanning electron microscopy to study the anatomy of the larvae of three trap-jaw ant species: Odontomachus bauri, Odontomachus meinerti (both found in Central and South America)and Odontomachus brunneus (found in the southern United States).

Larval phase

The researchers found that trap-jaw-ant larvae develop through three phases, or instars. Just after hatching, the larvae are whitish-yellow, with few body hairs but bizarre doorknob-shaped protuberances on their backs. In the second instar, the larvae lengthen and slim down, turning gray-beige and growing more hair-like spines. In the third instar, the doorknob protuberances vanish, but disc-like protuberances dot the larvae's backs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The doorknob protuberances are used to suspend the larvae from the walls and ceilings of their nests, the researchers reported in the journal Myrmecological News. By the third instar of development, the larvae were arranged on the nest floor instead.

In yet another weird discovery, the researchers found two larvae of Odontomachus bauri from French Guiana, each containing a developing parasite within its guts.

The findings are visually fascinating, study co-author Adrian Smith, a professor at North Carolina State University and an evolutionary biology researcher at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, said in a statement. They're also useful for studying how ants develop in colonies, Smith said.

"This research provides foundational knowledge, which enables future research questions on developmental trajectories," Smith said, "such as when an individual might switch from developing into a worker to developing into a queen."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular