'Organ Chip' Project to Test How Chemicals Affect the Body

Tiny replicas of organs, shrunk down to fit onto computer chips the size of AA batteries, could help doctors and scientists learn about how certain foods, chemicals and dietary supplements affect the human body, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says.

These "organ chips" have been in the works since 2012, the FDA said today (April 11) in a post on its blog. Other institutions, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), are also involved in the project.

Now, researchers at the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition are studying the chips, which are made by a company called Emulate Inc., according to the post. [5 Amazing Technologies That Are Revolutionizing Biotech]

Initially, researchers thought that the chips would be particularly helpful in research into how well drugs work in certain organs, Suzanne Fitzpatrick, senior adviser for toxicology in the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, wrote in the blog post. But the FDA also hopes to use the organ chips to study the safety of foods, cosmetics and dietary supplements, the agency said.

The information from these chips — which could show "how the body processes an ingredient in a dietary supplement or a chemical in a cosmetic, and how a toxin or a combination of toxins affects cells" — could help researchers assess whether the compounds pose a risk to human health, Fitzpatrick wrote.

What's in a chip?

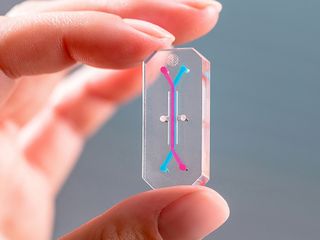

Each chip will represent one organ, according to the FDA, and the agency will begin its research using the "liver chip." In the future, the FDA and Emulate hope to develop kidney chips, lung chips and intestine chips. Because the chips are translucent, researchers will be able to observe what's going on inside them.

The chips are made from a flexible polymer material that's filled with tiny channels, according to the FDA. These channels are lined with living human cells from the organ being studied. For example, the liver chip contains liver cells. [11 Body Parts Grown in the Lab]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each chip is designed to mimic the natural physiology of the organ. In other words, the tiny channels in the liver chip could replicate blood flowing through the liver, and a lung chip would be designed to replicate breathing motions and muscle contractions, according to Emulate.

The chips can also be placed into a large instrument that helps re-create the environment inside the human body, according to Emulate. This way, scientists will be able to feed specific compounds, such as a chemical found in a food or a cosmetic product, into the chip, and see how the organ responds in the "human body," the company says. It may also be possible to connect several organ chips together, to study how chemicals affect multiple organ systems in the body, the company says.

But this is not the first time scientists have tried to replicate how organs work and react in the lab. In March, researchers at Northwestern University designed a device that can mimic a woman's menstrual cycle in the lab. They hope to use the device to learn more about conditions that affect women's health, such as fibroids, polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis.

Originally published on Live Science.