Bird-Eating Spiders: 3 Massive, Furry Tarantulas Discovered

Three new species of massive, furry "birdeater" spiders have been discovered, with dozens more stricken from the grouping.

In a new paper published in the open-access journal ZooKeys, researchers cleaned house on the genus Avicularia, a group of hairy tarantula spiders that was, in the words of lead study author Caroline Sayuri Fukushima, "a huge mess."

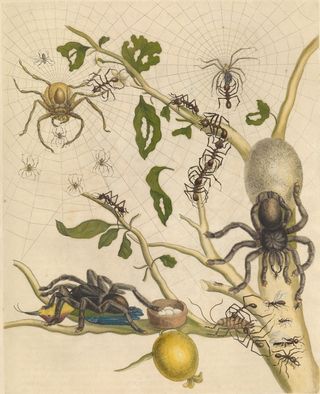

Fukushima, a researcher at the Instituto Butantan in São Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues sorted out the genus, which was first described in 1818. They narrowed the number of Avicularia species from more than 50 to 12, including three new species of Avicularia that hadn't been noted before. They named one of these species after Maria Sibylla Merian, a naturalist born in 1647 who famously painted an illustration of an Avicularia spider eating a bird. [See Amazing Photos of Goliath Birdeater Spiders]

"This illustration gave origin to the name of the genus and the popular name birdeater spiders," Fukushima told Live Science in an email. "People [in] that time did not believe in her observations, saying that a spider eating a bird was a female fantasy. But now we know she is right!"

A tangled web

Over the years, other scientists added more and more spiders to the genus, but no one ever had a good sense of what made a tarantula an Avicularia, other than that they are large and fuzzy, and live in trees, feasting on everything from insects to bats to small birds. Most Avicularia species grow around 5 or 6 inches (12 to 15 centimeters) in length, and many are popular pets for tarantula enthusiasts. [Ewww! See Photos of Bat-Eating Spiders]

"The reasons to do this work were the necessity of solving the many problems of the genus (which were causing confusion to other genera, too), but also the chance to do something hard, big, important and new regarding tarantula taxonomy," Fukushima wrote.

And hard it was. The project took years, Fukushima said. The researchers had to track down ancient specimens from museums around the world, puzzling out original descriptions in Latin, French, Dutch, Portuguese and German. The scientists compared the anatomical characteristics of these old identifications with those of spiders from modern zoos and museums.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Naming new spiders

Untangling the mess of Avicularia required creating a new genus, Ybyrapora, to encompass certain Brazilian spiders that dwell in rainforest trees, the scientists said. Researchers also moved two species of Caribbean spider that were previously in the Avicularia genus to a new genus called Caribena. Finally, the scientists established a new genus called Antillena for a species of Dominican Republic tarantula identified in 2013 as Avicularia rickwesti. The spider is large and mostly reddish, with a distinctive red "oak leaf" pattern on its black abdomen.

The discoverers of A. rickwesti wrote in the journal Zoologia at the time that the species was quite different, anatomically, from other Avicularia spiders, but noted that it didn't fit in any other genus, either.

The researchers also named three new species of spider in the Avicularia genus. One, A. caei, is found only in Brazil. Another, A. lynnae, can be found in Ecuador and Peru. A. merianae, found only in Peru, was given its name in honor of the naturalist Merian.

"Despite her great work for natural science, she is poorly recognized when compared with male naturalists of that time," Fukushima explained.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.