Smile! New Bucktoothed Ghost Shark Species Discovered

A previously unknown ghost shark with rabbit-like teeth and a bulky head is making waves in record books; it's the 50th ghost shark species known to science, a new study reported.

At nearly 3 feet (1 meter) in length — about half as long as the height of a refrigerator — the newfound creature is the second largest species of ghost shark ever discovered, the researchers said.

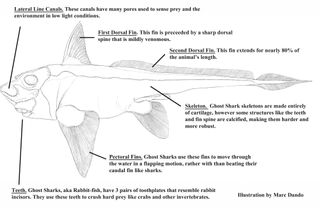

"[Ghost sharks] in general have a pretty big head and their body tapers to a thinner tail. This one was really chunky in the front, and just a big bulky specimen," said Kristin Walovich, a graduate student at the Pacific Shark Research Center at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories in California, and the lead researcher of a new study. [See Photos of the Freakiest-Looking Fish]

Like some other ghost sharks, the newfound species has rabbit-like buckteeth, prompting researchers to put it in the genus Hydrolagus, which translates to"water rabbit" or "water hare." (In Greek, "hydro" means "water" and "lagus" means "rabbit" or "hare.") The species name erithacus is the genus name for robin birds. That name was chosen for the new species to honor Robin Leslie of the South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, who helped Walovich study the ghost shark, Walovich said.

There are already three known species in the genus Hydrolagus — H. africanus, H. mirabilis and H. cf. trolli — that live in the same region as the new find, between South Africa and Antarctica in the southeastern Atlantic and southwestern Indian Oceans, the researchers said.

In fact, fishermen have been saying for years that individuals now called H. erithacus didn't look like the other known species, Walovich said. Two of the specimens in the new study came from deep-sea fishermen who mistakenly caught the animals as bycatch. But the other specimens included in the study had been sitting in a museum for years, she said.

"The scientists and the fishermen in South Africa knew this was not the same species, because Hydrolagus africanus is small, it's brown, and this one was huge and really dark in color," Walovich told Live Science. "Just visibly, they were definitely different species."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Despite their names, ghost sharks aren't actually sharks. Rather, the cartilaginous fish are relatives of sharks and rays. She noted that while sharks swim by moving their tails and rays literally "fly" underwater, ghost sharks use their large pectoral fins, located on both sides of their bodies, to propel themselves forward.

Scientists also call these animals chimaeras or ratfish, but little is known about them. Most chimaeras live in the deep sea, so researchers know little about their behavior, such as how often they reproduce.

However, Walovich made an exciting find that revealed something about the ghost shark's behavior. The stomach of one of the H. erithacus specimens contained a crab claw, indicating that the fish used its strong teeth to crunch open the shells of crabs and likely other crustaceans that live on the seafloor, Walovich said.

The study was published in the Jan. 31 issue of the journal Zootaxa.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.