SAN FRANCISCO — Syrian refugees fleeing civil war have flooded into areas of Turkey that are riven with dangerous earthquake faults, new research shows.

As a result, traditional seismic hazard maps may underestimate by 20 percent how many people could die in a cataclysmic quake, according to research presented here today (Dec.13) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

"The total scale of fatalities that the earthquake scenarios show are significant enough to potentially inspire some action," Bradley Wilson, a geoscientist at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, told Live Science. [Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

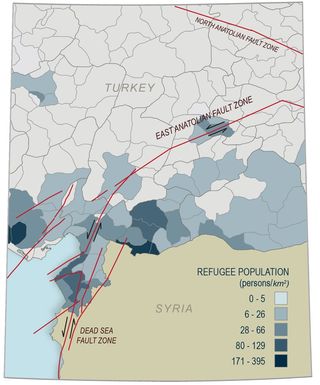

Over the last five years, Turkey has taken in more than 2.7 million Syrian refugees, according to the U.N. Refuge Agency. Many of these people have settled in areas that have experienced catastrophic earthquakes in the past.

However, typical seismic hazard maps may not include these newer residents.

To remedy that problem, Wilson used estimates of refugee population distribution collected by the State Department's U.S. Humanitarian Information Unit. Though the Humanitarian Information Unit keeps some of its methodology private, there are some basic elements to its population estimates. For instance, the Humanitarian Information Unit may combine data from registered refugees in camps, with surveys taken by workers on the ground, as well as aerial imagery, to estimate the number of refugees in particular districts of Turkey, according to Wilson.

It turned out that just 14 percent of the refugees lived in traditional tents or container refugee camps in Turkey, said Wilson, who's research is funded by a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship and a fellowship from the University of Arkansas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"A majority of the refugee population is not located in refugee camps and is distributed amongst the local cities and villages," Wilson said.

By combining that data with other population data, Wilson estimated the population before and after the Arab Spring, or the uprisings that spread across the Middle East in 2011 and escalated into the Syrian civil war, to see how the most seismically vulnerable areas of Turkey were likely to be affected by the resulting refugees. His model assumes that most of the refugees, like the rest of the population in Turkey, live in more urban areas, he said.

Next, Wilson estimated fatality rates from earthquakes of different magnitudes, from 5.8 to 7.0. If a magnitude-7.0 quake struck the population centers, the fatality rate could be 20 percent higher than otherwise would have been predicted, Wilson said.

The refugee influx also shifted the areas with the highest fatality risk. Before the refugee crisis, the area with the highest potential for fatalities was in the heart of the country. But after the crisis, the highest risk areas shifted farther south, near the Turkey-Syria border, the study found.

Still, there are some limitations to the study. The population estimates are inherently uncertain, and there isn't much data on earthquake resistance of the buildings where refugees are living, though another study of a refugee camp in Palestinian territory found the structures were typically not very resistant to strong shaking, he added.

It's also not clear whether the new findings on increased mortality will affect Turkey's efforts to seismically retrofit buildings and prepare for the next big one, he said. Previous research, published in 2014 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, has suggested that a segment of the North Anatolian Fault just west of Istanbul is likely to cause the next major earthquake there. However, nobody can predict when that might happen.

"Whether the 20 percent makes a difference for the Turkish government, I'm not quite sure," Wilson said. "But I still think the analysis has important implications for the hazards community."

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular