Unfrozen: Greenland Was Once Ice-Free for 280,000 Years

More than a million years ago, frosty Greenland was ice-free, its bare bedrock exposed for 280,000 years, researchers have found.

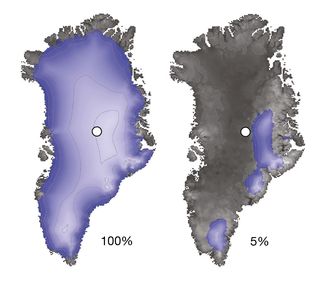

During this exposed stint, the island's overall ice cover could have dropped by more than 90 percent, the scientists reported today (Dec. 7) in the journal Nature.

Previous studies have reported that Greenland's ice shrank in the distant past, but this study is the first to explain how long a span Greenland may have endured without its usual frozen cover. This discovery hints that its surface ice was more variable than once thought — which does not bode well for its future stability in a warming world, the researchers said. [In Photos: Greenland's Ancient Landscape]

As valuable as moon rocks

The study authors gathered their data from isotopes — atoms of the same element but with a different number of neutrons — extracted from bedrock minerals. The isotopes, beryllium 10 and aluminum 26, are produced only by cosmic rays, which means that they only occur when the rock that holds them is exposed; as such they can offer clues about when rocks were bare of ice, and for how long.

These isotopes originated in the only rocky core ever extracted from land underneath Greenland ice, drilled at the Greenland Ice Sheet (GIS) summit in 1993.

Minerals from this solitary core are second only to moon rocks in their rarity and importance, as they are the only existing evidence of Greenland's ice-covered extant bedrock, according to lead author Joerg Schaeffer, a paleoclimatologist with the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and a professor with the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University.

When this core was first examined decades ago, researchers were able to detect isotopes in the sediment produced by cosmic rays, but their equipment wasn't sensitive enough to gather precise climate data, Schaeffer told Live Science. In order to get to the isotopes, "we literally digested those rocks," he said, describing how he and his colleagues dissolved minerals with acid so they could observe the atoms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The atomic isotope beryllium 10 told the scientists that the rock had at one point been ice-free. To gauge how long that period lasted, they compared the amount of beryllium to quantities of aluminium 26. It appears at a 7 to 1 ratio to beryllium 10, but decays twice as fast. The quantity of aluminium atoms relative to beryllium told the scientists that once the ice cover melted away, the rock was exposed for more than 280,000 years, until about 1.1 million years ago.

The extent to which Greenland's ice may have waxed and waned over time was the subject of another new study, also published today (Dec. 7) in Nature. Lead author Paul Bierman, a professor of geology at the University of Vermont, told Live Science that the study found evidence of ice covering the island for a period of 7.5 million years, a much longer period than described in any prior study.

A patchwork history

Though many scientists have investigated Greenland's ice for clues about its behavior over time, a comprehensive picture long remained elusive. And Greenland itself is to blame for this incomplete view, as recurring changes in ice cover scrub away geologic evidence over and over again, Bierman said. ['Dark Ice' Speeds Up Melting in Greenland (Photos)]

"Whenever the ice expands, it wipes away what it did last time," Bierman told Live Science. "It's like looking at a chalkboard that's been erased, and you have to figure out what happened three classes ago."

Bierman and his colleagues analyzed deep-sea samples from a core of weathered bedrock that originated in East Greenland, but was carried into the ocean off the coast.

Their examination revealed that during the past 7.5 million years, Greenland ice was "persistent" but also "dynamic," the scientists wrote in the study, allowing that there were likely periods when the ice cover dwindled due to global temperature changes.

Addressing uncertainties

While Bierman's study suggests that ice consistently blanketed Greenland, that doesn't necessarily rule out that some parts of the island were ice-free at times. High-altitude regions in the east could have stayed frozen even during warm conditions, while other parts of Greenland lost their ice, according to Ginny Catania, an associate professor with the Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

Catania, who was not involved in the new studies, told Live Science in an email that both investigations support reduced ice in Greenland's past, but more data would be required to understand the processes that contributed to massive and rapid ice loss, and how they might drive future melt. [5 Places Already Feeling the Effects of Climate Change]

"These uncertainties limit our ability to accurately predict the future of the ice sheet," Catania said. "We are in for a lot of change in Greenland in the future. The question remains — how quickly will it happen?"

Techniques used in both studies introduce novel methods for looking at how Greenland's ice changed, but there is still more work to be done. Determining more precisely when and why historical ice loss happened could greatly improve computer models that would find a threshold for instability in Greenland's ice today, according to Anders Carlson, an associate professor of geology and geophysics with the College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University.

"Regardless of when Greenland had ice-free conditions, the ice sheet has been unstable and collapsed in the past," Carlson told Live Science. "And that probably occurred when CO2 [carbon dioxide] levels were below what they are now — which bodes ill for future," he said.

And time may be running short. Seasonal melt for Greenland in 2016 was above average, with the third highest surface mass loss of ice in 38 years of satellite observations, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Were Greenland to lose the majority of its ice, as it did in the past, the water released into the world's oceans could produce around 23 feet (7 meters) of sea level rise, Schaeffer added.

"We have never seen the planet warming as fast as it is now, and we have to prepare as best we can," Schaeffer told Live Science. "We need to get organized quickly, and, hopefully, this helps to make the case."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular