8 Galaxies With Unusual Names

"Loopy" Galaxy

What's in a name? When it comes to catchy monikers, most galaxies come up short.

But perhaps that isn't so surprising. With an estimated 100 billion to 200 billion galaxies in the known universe, it's no wonder that the majority of galaxies that have been identified thus far go by a catalog number: M51, GN-z11, and IOK-1, for example. Those arrangements of numbers and letters are loaded with meaning for astronomers, but they don't exactly inspire the imagination.

However, a handful of galaxies have fared a little better in the naming department — usually the ones that are distinctively shaped, extremely close by and easy to observe, or just exceptionally photogenic. Here's a look at some of these galaxies with standout names.

Milky Way Galaxy

Our home galaxy, the Milky Way, measures 100,000 light-years in diameter, and is thought to contain at least 100 billion stars and possibly as many as 400 billion or more. It is a barred spiral galaxy, with a central bar structure running across its core.

Though the Milky Way was long thought to have only two spiral arms, a 12-year study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 2013 confirmed that the galaxy has four major arms. Our sun and solar system are located on a minor structure known as the Orion Arm, about 26,000 light-years from the Milky Way's center.

Thousands of years ago, the Milky Way's bright sprawl of stars, dust and gas stretching across the night sky inspired the ancient Greeks to lend it a milky name, though historians are uncertain as to when it was first referred to as the Milky Way, according to Matthew Stanley, a professor of the history of science at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University.

Read more about the Milky Way and how it got its name

Tadpole Galaxy

A close encounter with another galaxy disrupted the spiral galaxy Arp 188, commonly known as the Tadpole Galaxy. Like its aquatic eponym, the Tadpole has an oval "head" — the main part of the spiral — and a long, trailing "tail."

The sweeping appendage measures about 280,000 light-years in length and is studded with enormous and brilliant star clusters. It likely formed when another galaxy approached too close to the Tadpole and was swung around behind it by gravitational forces. That same attraction probably teased out the ribbon of stars and gas that now trails behind the Tadpole, according to a NASA description.

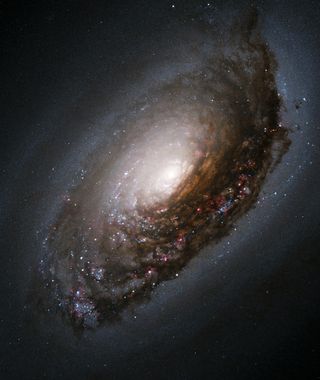

Black Eye Galaxy

Messier 64 (M64) has a somewhat sinister common name: the Black Eye or Evil Eye Galaxy, inspired by the dark band of dust surrounding its bright core. This shadowy band likely formed after a collision with another galaxy.

In the 1990s, scientists discovered that gas in the Black Eye's outer regions was rotating counterclockwise — the opposite direction from the gas and stars closer to the center. Astronomers suspected that this unusual region is the last remnant of a smaller galaxy that collided with the Black Eye over a billion years ago, and was gradually absorbed.

The Black Eye is located in the constellation Coma Berenices, approximately 17 million light-years from Earth, and was catalogued by French astronomer Charles Messier in the 18th century.

Sombrero Galaxy

The Sombrero is a spiral galaxy, and its unusual hat-like shape is suggested by our perspective on its position in space, viewed edge-on from Earth. This creates the illusion of a hat's "brim" — the outermost ring of stars — and a "crown" where the luminous core bulges at the center, circled by darker lanes of dust.

Also known as Messier 104 (M104), the Sombrero is located about 28 million light-years from Earth and measures 50,000 light-years across. It is one of the most massive objects in the Virgo cluster — as big as 800 billion suns, according to the Hubble Space Telescope website.

Whirlpool Galaxy

Like our own Milky Way, the Whirlpool (Messier 51, or M51) is a spiral galaxy — the most common galaxy type, representing about 77 percent of all galaxies in the universe — with multiple arms curving outward and wrapping around a bright center. Its yellowish core is home to older stars, while younger and brighter stars are visible along its arms.

The arms of the Whirlpool — as in all spiral galaxies — are stellar nurseries, where infant stars are born. At only 25 million light-years from Earth and measuring 60,000 light-years across, the Whirlpool is highly visible to astronomers and has been called one of "astronomy's galactic darlings" by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI).

Stellar deaths have been detected in the Whirlpool, as well. Observers reported three supernovas — a star's explosive demise — occurring in the Whirlpool during the past 17 years: in 1994, 2005 and 2011.

Cigar Galaxy

Located in the Ursa Major constellation about 13 million light-years from Earth, the Cigar Galaxy was named for the long, elliptical shape of its disk, which is how it appears relative to our sight line.

Also called Messier 82 (M82), the Cigar is known as a starburst galaxy — one with an exceptionally high star birth rate. In its central regions, stars are produced 10 times faster than in the Milky Way Galaxy, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

This six-image composite mosaic — the sharpest wide-angle view ever obtained of the Cigar Galaxy — was assembled from images taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, in March 2006.

Cartwheel Galaxy

Resembling an oversize wagon wheel, the Cartwheel Galaxy is estimated to measure 150,000 light-years across. It has a bright center with wispy "spokes" of dust and gas radiating outward to a surrounding ring of stars, which is about 1.5 times the size of the Milky Way, according to the Hubble Space Telescope website.

The Cartwheel's unusual shape was caused by a dramatic, head-on cosmic collision millions of years ago, according to a description on the Chandra X-Ray Observatory website. It was originally a large spiral galaxy, but a smaller galaxy perforated its center, disrupting stars much like a stone dropped in water causes outward-spreading ripples.

It is located 500 million light years from Earth, in the Sculptor constellation.

Sunflower Galaxy

Galaxy Messier 63 (M63), also known as the Sunflower Galaxy, was the 63rd entry in French astronomer Charles Messier's catalog of celestial objects, published in 1781, and was given its flowery name for the tight spiraling of its many arms, which was thought to be reminiscent of the pattern at a sunflower's center.

The Sunflower is about 27 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Canes Venatici — "The Hunting Dogs" — and is part of the M51 Group, a collection of galaxies that also appears in Messier's catalog and is named for Galaxy M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy.

The brilliant glow that illuminates the Sunflower's spirals is generated by newly formed blue-white giant stars, according to the Hubble Space Telescope website.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.