Ancient Bird Coughed Up 'Fishy' Pellet 120 Million Years Ago

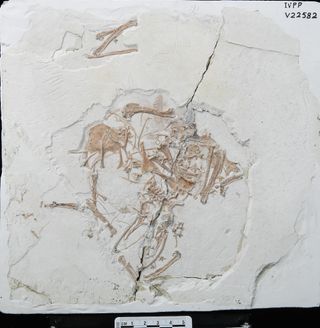

SALT LAKE CITY — About 120 million years ago, a bird dunked its beak into the water, caught a fish and, after digesting the meal, coughed up a pellet full of fish bones. The bird died moments later, but now its fossils are the oldest evidence of a bird pellet on record, a new study reported.

The pellet — the first that is unambiguously from a bird that lived during the Mesozoic, the age of the dinosaurs — indicates that the ancient bird had a two-chambered stomach, much like birds do today, the researchers said.

Modern-day birds, including many birds of prey, produce pellets made up of indigestible material, such as bones, hair and feathers. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly (Gallery)]

"The very presence of the gastric pellet in the new specimen indicates that some key features of the modern birds' digestive systemhad already appeared in these early Cretaceous birds over 120 million years [ago]," said the study's lead author, Min Wang, an associate professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. (The Cretaceous Period was the last part of the Mesozoic Era and spanned from 145 million years ago to about 66 million years ago.)

The stunning specimen was found in 2014 in the Jiufotang Formation, located in northeastern China's Liaoning Province. After examining the animal's anatomy, Wang and his colleagues determined that the bird belonged to the enantiornithes, the most diverse group of Mesozoic birds, Wang said.

Despite the number of enantiornithes fossils that researchers have uncovered over the past three decades, "only this new specimen provides the direct evidence that some enantiornithine birds were piscivorous (ate fish)," Wang wrote. He noted that another enantiornithine bird dating to the Cretaceous period in modern-day Spain has crustacean exoskeletons in its digestive tract, providing more evidence that some of these ancient birds dined on marine animals."Their fossilized materials have been discovered from every continent except the Antarctic," Wang told Live Science in an email.

An array of modern animals cough up pellets; this includes many raptors and seabirds, as well as crocodilians, squamates (scaled reptiles) and some marine mammals, Wang said. These animals still pass waste, but their pellets contain other indigestible food items, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The digestive system of living birds are characterized by a two chambered-stomach with a muscular gizzard capable of compacting indigestible matter into a cohesive pellet, and efficient antiperistalsis," the process of "coughing up" the pellet, Wang said. "Our discovery suggests that all these features are present in some early Cretaceous birds … [and] thus key features of modern birds' digestive system occurred earlier than we thought."

The study was published in May in the journal Current Biology, and was presented Wednesday (Oct. 26) at the 76th annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular