In people with Alzheimer's disease, a new investigational drug can dramatically reduce the amount of amyloid beta plaque, the tangled clumps of proteins that form in the brains of Alzheimer's patients, according to a new early study of the drug.

The drug works by spurring the immune system to recognize and clear the plaques.

"We believe that's a hint of efficacy," study co-author Dr. Alfred Sandrock, a neurologist and an executive vice president at Biogen, said during a news briefing. "We believe that needs to be confirmed with further studies." Biogen is the Cambridge, Massachusetts, company that funded the trial and applied to patent the drug. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

However, the study was too small to show whether there was an effect on the patients' symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. And the drug can also cause fluid accumulations in the brain in some genetically susceptible people, the researchers reported today (Aug. 31) in the journal Nature.

Cause of dementia

Alzheimer's disease is the leading cause of dementia, affecting more than 5 million people in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The hallmark of the disease is aggregation of an abnormal protein called amyloid beta, which looks like clumps of tangled fibrils on brain scans. Many scientists believe the amyloid beta fibrils are toxic to brain cells and are directly responsible for the memory loss, mood changes and loss of function that occur as the disease progresses, according to the paper.

There is no cure for Alzheimer's, and the few treatments on the market have only modest, transient benefits.

Targeting amyloid beta

To find a better treatment, Sandrock and his colleagues at Biogen turned to older people who do not have dementia or Alzheimer's. They analyzed the chemicals present in healthy older people with no cognitive decline, as well as people whose cognitive decline had progressed very slowly. The team identified one immune compound, and made a drug that mimicked it, called aducanumab. In earlier animal studies, the drug seemed to target amyloid beta and spur other structures in the brain to engulf and clear the plaques, Sandrock said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

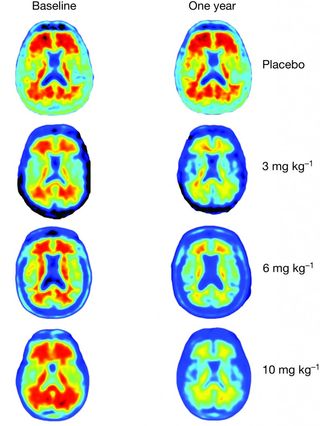

In the new study, researchers gave 165 patients with mild Alzheimer’s monthly infusions of either aducanumab or a placebo, and did a series of brain scans. The people taking aducanumab showed a sharp decrease in the amount of amyloid beta in their brains. The higher the dose of aducanumab they received, the greater the amyloid clearance revealed in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

"After one year, you can see no red on the image, meaning the amyloid has almost completely disappeared," said Dr. Roger Nitsch, a co-author of the study and the director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Zurich. He is also a founder of the biopharmaceutical company Neuroimmune.

However, people who took the drug, and also carried a genetic change called the APOE gene variant, which is linked with Alzheimer's disease, were also more likely to experience a potentially dangerous side effect known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA. This side effect showed up in brain scans as small pockets of fluid in the brain.

Although most people in the study who developed ARIA were asymptomatic, a few patients reported headaches. Studies in other Alzheimer's drug candidates have shown that in rare cases, ARIA can increase the risk of stroke or cerebral hemorrhage, the researchers said. ARIA, if it does occur, usually shows up early in treatment and can be managed and cleared by lowering the drug dose, Sandrock said.

Cognitive benefits unclear

The study was not designed to show whether the drug can actually produce cognitive benefit; however, the team found hints of cognitive benefit that did not reach statistical significance.

"We're encouraged that, there appeared to be a slowing of cognitive decline at a dose-dependent manner, and also a dose-dependent slowing in functional decline," said study co-author Dr. Stephen Salloway, a neurologist at Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

Much larger follow-up studies are needed to confirm that the benefit is real, Salloway said.

Indeed, the larger question is whether clearing amyloid beta will lead to dramatic improvements in cognitive decline, Dr. Eric Reiman, a psychiatrist and researcher at Banner Alzheimer's Institute, a research and patient care center in Phoenix, wrote in an editorial accompanying the new study in the journal. Some researchers believe beta amyloid is a byproduct of the destructive brain process, and not the cause, noted Reiman, who was not involved in the new study.

If larger trials of the drug show improvement in patients' cognitive function, that will help settle the debate on whether amyloid beta causes Alzheimer's, Reiman said.

"It would be prudent to withhold judgment about aducanumab's cognitive benefit until results from the larger trials are in," Reiman wrote in the article.

What's more, by the time people begin to show symptoms, it's thought that they have been accumulating plaque for 15 years and much of the cognitive damage may have already occurred, Sandrock said.

So eventually, this drug or another one like it, could be most effective when people first show signs of plaque accumulation, but have no cognitive symptoms, he speculated.

"I still think that treating early is going to be the key," Sandrock said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.