Why David Bowie Was So Loved: The Science of Nonconformity

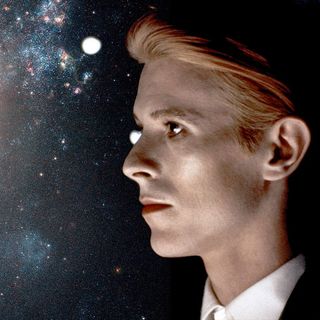

In the aftermath of David Bowie's death at age 69 from cancer, a re-occurring theme has appeared in tributes to the famously idiosyncratic performer: his importance to those who felt like misfits.

"Yes, I'm obsessing about Bowie today," tweeted science writer Steve Silberman. "To the terrified gay kid I was in high school, he was a proud and flamboyant middle finger to bullies."

Across both social and conventional media, other lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender artists echoed Silberman's words. "Bowie made me feel OK with my weirdness," bisexual actress Giovannie Espiritu told The Daily Dot.

In fact, Bowie's androgyny, theatrical style and tendency to reinvent himself resonated with LGBT people and many others. [5 Myths About Gay People Debunked]

"He was so important for all of the people who felt different, who felt like outsiders, who felt like their identities, for whatever reason, weren't recognized and loved," said Angela Mazaris, the director of the LGBTQ Center at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

The outpouring of grief over Bowie's death shows just how important such recognition can be. But research has shown the same thing. Humans, even as they crave acknowledgement as individuals, find it important to see others who are like them.

Fitting in

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The need to conform starts young. Researchers reporting in a 2014 study compared the behaviors of 2-year-old children with those of chimpanzees and orangutans. Both the apes and human children were shown a toy box that, if used correctly, would dispense a treat. After learning how to get the treats, the participants watched other kids or apes use the box in a different, non-treat-dispensing, way. The other kids or apes then watched as the original participant got the chance to play with the treat box again.

Subsequently, the apes continued their tried-and-true method of getting treats from the box. But 2-year-olds switched their method 50 percent of the time, researchers reported in the journal Psychological Science. The toddlers were more likely to copy others' behavior when their peers were watching them play than when alone.

"We were surprised that children as young as 2 years of age would already change their behavior just to avoid the relative disadvantage of being different," study researcher Daniel Huan, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, said in a statement.

Multiple studies have found that people gravitate toward others like them. One 2014 paper revealed that people even like those with voices and speaking styles similar to their own. Even infants choose puppets that like the foods kids like, found research by Yale University psychologist Karen Wynn. A 2013 study out of Wynn's laboratory showed that babies prefer puppets that are nice to individuals who resemble the kids (in this case, still based on food preferences) and mean to individuals not like the children.

An alternative conformity

In light of this strong psychological predisposition for conformity, David Bowie was a ray of glamorous, sequin-studded light. [10 Celebrities with Chronic Illnesses]

"When you read accounts of people who remember seeing David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust for the first time, they talk about this sort of awakening," Mazaris told Live Science. The rocker's bisexual alien alter ego portrayed androgyny and nonheterosexual sexuality as beautiful and worth celebrating, she said.

"I think it's about being able to imagine possibilities for yourself and your identity," she said.

Representation appears to be important for helping people feel they fit in. For example, research on women in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields finds that female role models help to keep women from underperforming. For example, one 2002 study published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that when a woman administered a math test to female students, the women were less likely to struggle with the test because of situational factors (like anxiety caused by the knowledge of the stereotype that women are bad at math).

A 2011 study in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science found that the role-model effect is about more than just gender. Individual information, such as whether a role model fits "nerdy" stereotypes, was more important than the gender of the role model in encouraging women to believe in their ability to succeed in computer science.

Likewise, the very public world of celebrities and media can influence how people view themselves. A study published in November 2014 in the International Journal of Educational Research found that negative media portrayals of Islam harmed the well-being of Muslim international students in the United Kingdom.

And exposure to negative portrayals of a certain group can stir up animosity from other groups. One 2015 study found that just watching local news in which crimes committed by African-Americans were overrepresented gave people more negative attitudes toward black people.

For LGBT people, particularly those who don't feel they fit into the male/female gender binary, Bowie provided the kind of positive representation that had been sorely lacking, and is still somewhat unusual today, Mazaris said.

"He really showed us that there are so many ways to be a star," she said.Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular