Plague Began Infecting Humans Much Earlier Than Thought

The germ that causes the plague began infecting humans thousands of years earlier than scientists had previously thought.

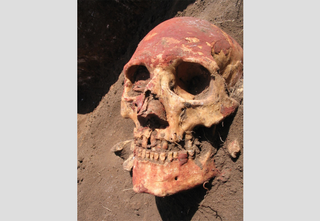

Researchers analyzed teeth from the remains of 101 individuals that were collected from a variety of museums and archaeological excavations. They found DNA of the bacterium that causes plague, called Yersinia pestis, in seven of these people. The earliest sample that had plague DNA was from Bronze Age Siberia, and dated back to 2794 B.C., and the latest specimen with plague, from early Iron Age Armenia, dated back to 951 B.C.

Previously, the oldest direct molecular evidence that this bacterium infected humans was only about 1,500 years old.

"We were able to find genuine Yersinia pestisDNA in our samples 3,000 years earlier than what had previously been shown," said Simon Rasmussen, a lead author of the study and a bioinformatician at the Technical University of Denmark.

The finding suggests that plague might be responsible for mysterious epidemics that helped end the Classical period of ancient Greece and undermined the Imperial Roman army, the researchers said. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The new study also sheds light on how plague bacteria have evolved over time, and on how it and other diseases might evolve in the future, the investigators added.

Plague is a lethal disease so infamous that it has become synonymous with any dangerous, widespread contagion. It was one of the first known biological weapons — for instance, in 1346, Mongols catapulted plague victims into the Crimean city of Caffa, according to a 14th-century Italian memoir. The germ is carried and spread by fleas, as well as person-to-person contact.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yersinia pestis has been linked with at least two of the most devastating pandemics in recorded history. One, the Great Plague, which lasted from the 14th to 17th centuries, included the notorious epidemic known as the Black Death, which may have killed up to half of Europe's population at the time.

Another, the Modern Plague, began in China in the mid-1800s and spread to Africa, the Americas, Australia, Europe and parts of Asia. Moreover, the Justinianic Plague of the 6th to 8th centuries, which killed more than 100 million people, may have helped to finish off the Roman Empire.

Pandemics that struck hundreds of years before those plagues are sometimes blamed on Yersinia pestis as well. These include the Plague of Athens, which occurred nearly 2,500 years ago and was linked with the decline of Classical Greece, and the Antonine Plague of the second century, which devastated the Imperial Roman army. However, it remains unclear whether plague bacteriacould have indeed caused these ancient epidemics, because scientists have not seen any direct molecular evidence of this germ from skeletons older than 1,500 years.

In the new study, researchers looked at DNA sequences in tooth samples from Bronze Age people from Europe and Asia. The finding that people were infected with plague about 4,800 years ago suggests that the disease could have influenced human history much earlier than previously thought, the researchers said.

The scientists also found that plague has changed in its deadly ways over time. For instance, plague genomes from the Bronze Age, which began around 3000 B.C., lacked a gene called the ymt gene. This gene is involved in protecting the bacterium when it is inside the guts of fleas, thus helping the insects spread the plague to humans.

However, this gene was found in the plague bacteria in the sample from the Iron Age, which began almost 2,000 years later. This finding suggests that plague bacteria became transmissible by fleas sometime during or after the Bronze Age, conflicting with previous research suggesting that the ymt gene emerged early in the evolution of plague due to its importance in the germ's life cycle.

The researchers also learned more about how plague has evolved to stealthily evade human defenses. In mammals, the immune system can recognize and mount offensives against a protein called flagellin, which is the key ingredient of the flagellum, the whiplike appendage that helps bacteria move around. All previously known plague strains had a mutation that prevented them from producing flagellin. The two oldest Bronze Age individuals lacked this mutation, but it was seen in the youngest Bronze Age individual.

"We are able to investigate the early evolutionary steps of what developed into one of the deadliest bacteria ever encountered by humans," Rasmussen told Live Science.

Together, these findings suggest that plague did not fully emerge as a highly virulent flea-borne germ until about 3,000 years ago. The genetic changes that plague underwent may have not only helped give rise to infamous epidemics, but also driven large migrations and resettlements by people living in both Europe and Asia during the Bronze Age.

"Perhaps people were migrating to get away from epidemics or recolonizing new areas where epidemics had decimated the local populations," Morten Allentoft, another lead author of the study and an evolutionary biologist at the University of Copenhagen, said in a statement.

The underlying mechanisms that helped plague evolve over time "are still present today, and learning from this will help us understand how future pathogens may arise or develop increased virulence," Rasmussen said in a statement.

In the future, the researchers will look for evidence of plague and other germs in other places and times around the world to get a better grasp of the history of the diseases. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

"The underlying evolutionary mechanisms that facilitated the evolution of plague are still present today," Rasmussen told Live Science. "By knowing which new genes and mutations lead to the development of plague, we may be better at predicting or identifying bacteria that could develop into new infectious diseases.

The researchers detailed their findings today (Oct. 22) in the journal Cell.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.