ST. LOUIS — The next factory for lifesaving drugs could be the human body itself.

Scientists are developing a new vaccine-making method that co-opts the human body's ability to quickly create antibodies, its main weaponry for fighting disease, say researchers with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

The new method of vaccine production would involve giving the body instructions for making certain antibodies. Because the body would be its own bioreactor, the vaccine could be produced much faster than traditional methods and the result would be a higher level of protection, said Col. Daniel Wattendorf, a clinical geneticist with DARPA, the branch of the U.S. Department of Defense charged with developing new technologies for the military.

Wattendorf described his research here at the "Wait, What? Technology Forum," a conference hosted by DARPA. [Ebola Virus: 5 Things You Should Know]

Slow, ineffective process

The current process for producing vaccines takes at least nine months. When the H1N1 swine flu spread in 2009, researchers grew the vaccines in mouse ovaries for months before they could produce sufficient quantities of the drug to administer to people.

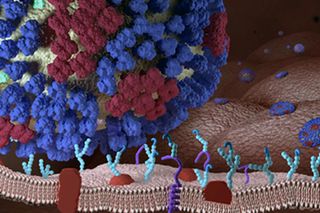

Ideally, the body will mistake the vaccine — essentially a harmless protein, or antigen, from the outer coat of the virus — for the virus itself. This case of mistaken identity then spurs the immune system to produce millions of antibodies, which latch onto and neutralize the invaders. Unfortunately, in the 2009 outbreak, only 40 to 60 percent of those who were immunized developed antibodies, Wattendorf said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When scientists crunched the numbers, they found the glacially slow production process, plus the limited vaccine effectiveness, meant the 2009 influenza vaccine protected just 1.6 percent of the 60 million-plus Americans who got the flu shot, Wattendorf said.

"And this was the fastest vaccine ever produced," he added.

Instant protection

But last year's Ebola crisis points the way to a potentially faster method. After the medical missionary, Dr. Kent Brantly, successfully fought off the deadly virus following a plasma transfusion from a patient, he returned the favor by donating his blood to other infected Americans.

Because his body had vanquished the virus, it was teeming with Ebola antibodies. In theory, this would instantly provide recipients with the weapons needed to destroy the virus. Unlike a typical vaccine, this method doesn't rely on the spotty ability of the immune system to recognize a foreign invader and then produce the most potent antibody, Wattendorf told Live Science.

But this Good Samaritan method has an obvious Achilles' heel: there won't always be willing, recovered patients to donate plasma in a pandemic that's spreading like wildfire, Wattendorf said.

Body as bioreactor

Instead, DARPA scientists are working on a more scalable method: Using living, breathing humans as their own antibody factories. [5 Dangerous Vaccination Myths]

Scientists would harvest viral antibodies from someone who has recovered from a disease such as flu or Ebola. After testing the antibodies' ability to neutralize viruses in a petri dish, they would isolate the most effective one, determine the genes needed to make that antibody, and then encode many copies of those genes into a circular snippet of genetic material — either DNA or RNA, that the person's body would then use as a cookbook to assemble the antibody.

Using a single needle jab, doctors would then insert the genetic antibody recipe into someone's muscle cells. Once inside the muscle cell, free-floating RNA would latch onto the DNA or RNA instructions and make many, many copies of antibodies. (Using RNA to encode instructions for making the antibody would quickly ramp up antibody production to an effective dose within a few hours, but the protection may dissipate quickly. DNA takes a day or two to produce antibodies and must be inserted via a more painful process called electroporation, but the antibodies will continue to circulate for months, Wattendorf told Live Science.)

"The body becomes the bioreactor," Wattendorf said.

In the works

So far, a number of different companies and institutions are developing potential vaccines using this method. Unlike gene therapy, the genetic instructions for making the antibody are not encoded into a person's genome permanently, he added. Instead, the genetic instructions for making the antibody are gradually degraded over time.

"We've done this for flu, and we're doing this with the Ebola patients who survived in the U.S.," Wattendorf said. "Particularly with flu, we've seen over 1,000-fold more potent protection than has ever been reported."

Right now, researchers have shown that using the body as a bioreactor can produce enough antibodies to protect small animals, such as mice and even nonhuman primates. But humans are bigger and require more circulating antibodies to fight off a disease, so researchers are currently exploring whether the current method produces enough antibodies for a therapeutic dose. The researchers have also received funding for early-phase safety testing in human trials, Wattendorf said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.