An Asteroid Didn't Wipe Out Ichthyosaurs — So What Did?

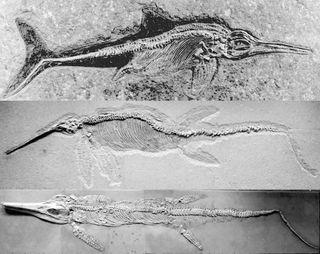

During the dinosaur age, ichthyosaurs — large marine reptiles that look like dolphins — flourished in prehistoric oceans, living in all kinds of watery environments near and far from shore. But as competition in these areas grew, ichthyosaurs lost both territory and species before gradually going extinct, a new study finds.

In fact, the ichthyosaur extinction has stumped scientists for years. Ichthyosaurs likely evolved from land reptiles that dove into the ocean about 248 million years ago, researchers said. After living along the coast for millions of years, they left for the open water. They disappeared about 90 million years ago, going extinct about 25 million years before the dinosaur-killing asteroid slammed into Earth.

So, if the asteroid didn't kill the ichthyosaurs, what did? To learn more, researchers looked at ichthyosaur fossils and determined what kinds of specialized environments, or niches, the animals likely inhabited. [In Images: Graveyard of Ichthyosaur Fossils Found in Chile]

"In most studies, the niche of the animal is predicted based on a single trait, usually the shape of the teeth," said lead researcher Daniel Dick, a doctoral student in paleontology at the Natural History Museum in Stuttgart, Germany. In the new study, the researchers looked at several traits, he said.

For instance, they analyzed the ichthyosaurs' body sizes and teeth shapes. They also determined each animal's feeding strategy, such as whether ichthyosaurs were ambush predators (less powerful swimmers) or pursuit predators (fast swimmers), Dick said.

Ichthyosaur arrangements

After examining 45 ichthyosaur genuses, Dick and his colleague Erin Maxwell, a vertebrate paleontologist at the museum, used an analysis that grouped the ichthyosaurs into seven categories, called ecotypes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, the ichthyosauriform genus, Cartorhynchus, is so unique that it has its own ecotype. It was likely a small suction feeder and lived in shallow water, Dick told Live Science.

Another ecotype represents the majority of the genuses that lived during the Early to Middle Triassic period, he said. Animals of this ecotype were less than 6.5 feet (2 meters) long, and had robust and blunt teeth, suggesting they ate hard-shelled prey, such as coral and shelled mollusks, Dick said. They didn't have elongated bodies, so they probably didn't live in the open water, where they would have needed to swim far distances, he added.

Two genuses — Eurhinosaurus and Excalibosaurus — owe their unique ecotype to their swordfishlike jaws, which indicate they used a slashing method to demolish prey, Dick said. Their long bodies also indicate they lived in the open water, far from shore, he said.

Not all seven ecotypes existed at once, although five existed simultaneously during the Early Jurassic period, when ichthyosaurs experienced a boom in diversity.

By the Middle Jurassic, the number of ichthyosaur ecotypes decreased. Specialized feeders, such as the swordfishlike Eurhinosaurus, and apex predators, including Temnodontosaurus, went extinct, leaving only two ecotypes, both of which lived in the open water.

These last two ecotypes included ichthyosaur genuses with large bodies and robust teeth for crushing bony fish or hard cephalopods, such as ammonites. The other ecotype was more dolphinlike; it had small teeth and likely ate soft prey, such as squid (also cephalopods), Dick said.

Ichthyosaur extinction

Ichthyosaurs eventually met their end during the Cenomanian-Turonian extinction event, in which spinosaurs (carnivorous swimming dinosaurs), plesiosaurs (long-necked marine reptiles) and roughly one-third of marine invertebrates (animals without a backbone) also went extinct, Dick said. [In Images: Digging Up a Swimming Dinosaur Called Spinosaurus]

With only two ecotypes of ichthyosaurs left, they would have been easily wiped out, Dick said.

"It's a slow ecological war of attrition, where they become more and more stranded on a single niche, and then the entire [group] is depending on that niche remaining sustainable," he said. "And if that became unsustainable, then the entire group would become extinct."

It's unclear why ichthyosaurs lost their earlier niches, but they were likely "replaced, outcompeted by other species that adapted better," Dick said. For instance, plesiosaurs took over many of the near-shore niches, he said.

The study sheds light on ichthyosaurs' evolution and extinction, said Neil Kelley, a postdoctoral research fellow of paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the new research.

According to the study, "[ichthyosaurs] get more and more confined to a specialized lifestyle," Kelley said. "Ultimately, they can never seem to re-evolve some of these more transitional lifestyles and body types that you see early on."

However, the study takes a broad view encompassing roughly 158 million years, so it loses some nuance in how these animals lived and why they went extinct, Kelley told Live Science. Furthermore, "just one weird fossil could totally rewrite that picture of what happened," by adding another ecotype, Kelley said.

The study was published online July 8 in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular