Common Dietary Supplements Don't Help Arthritis

The natural supplement combo of glucosamine and chondroitin, taken to relieve arthritis pain, has struck out again, proving to be no more effective than a placebo.

The people taking sugar pills, in fact, were better off by study's end with less pain and cartilage loss.

The study, in the October issue of the journal Arthritis & Rheumatism, highlights two important facts in the world of biomedical research. One is that scientists really do want to find safe, inexpensive and effective treatments for various diseases and will conduct high-quality studies to test their efficacy. There's no drug-company conspiracy keeping natural medicines off the market. Cheap vitamin fortification was one of the greatest public health accomplishments of the 20th century. The glucosamine and chondroitin study is part of an ongoing trial costing over $12 million and involving nine universities and medical centers. Results from 2006 also found no benefit from the two supplements.

The other lesson is that sometimes diseases are just too complicated to be treated with herbal tea. Modern pharmacology has been vastly successful in improving the quality and length of the lives of hundreds of millions of people with rare or common diseases. Kids used to die from leukemia, for example; now most of them don't.

But before I get too snarky, I should note the celecoxib, the multifaceted anti-inflammatory prescription drug marketed as Celebrex that possibly kills people with weak hearts (a 20,000-patient study is planned) worked only marginally better than the placebo in this glucosamine-chondroitin study. So, in theory, your knees won't hurt when you fall to the ground stricken by a heart attack.

The one-two missed punch

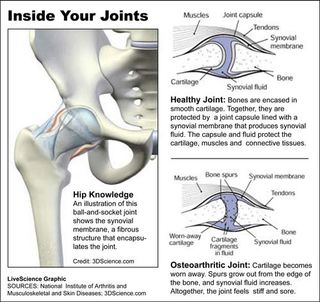

Glucosamine and chondroitin have been used together or individually for years to relieve the pain caused by osteoarthritis, the accelerated wearing of the cartilage cushioning the space between joints. As for as dietary supplements go, it is plausible these two compounds could treat osteoarthritis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Glucosamine, usually made from ground up shellfish, is a chemical precursor to glycosaminoglycans, the main ingredient of joint cartilage. Chondroitin sulfate is another component of cartilage that provides resistance to compression.

But the million-dollar question for these or any dietary supplement is can you eat it, have it melt in your stomach acid, have it be absorbed into your blood, and have it migrate magically to where it needs to go — in this case, to the cartilage between your joints, as opposed to the cartilage giving structure to your ears or nose.

So far the answer seems to be probably not, without an inkling of understanding what dose and what combination for what stages of osteoarthritis?

Something from nothing

Yet the study of glucosamine and chondroitin, which do appear to help some people sometimes, could lead to a better arthritis drug. Many prescription drugs are indeed based on natural substances refined to be more effective.

Shark cartilage provides an instructive example. The 1992 book "Sharks Don't Get Cancer" set off a craze for shark cartilage, with the theory posed by author William Lane that sharks don't get cancer because their skeleton is made of cartilage, not bone.

Turns out that sharks do get cancer, including cartilage cancer. Turns out, also, that Lane's son owned the company selling the shark cartilage. Nice. And it turns out that Lane fooled lots of people, even the television news program 60 Minutes, which helped fuel the craze by trumpeting Lane's unorthodox, lackluster and unpublished medical study in Cuba.

All cartilage has the ability to thwart angiogenesis, the growth of blood vessels important for health but exploited by tumors to grow and spread. This has been known since the early 1970s. Over a dozen clinical trials have been conducted, in fact, to test whether cow or shark cartilage can slow or kill cancer. (More proof that biomedical researchers would love a cheap cure.)

Thirty-some years and thousands of shark carcasses later, no amount of shark cartilage seems cure cancer. But researchers now are studying proteins in cartilage responsible for shutting down angiogenesis with the hope of creating drugs that can selectively halt the growth of blood vessels around cancer cells.

Maybe someday glucosamine and chondroitin will lead to arthritis relief, however circuitous. We'll need it. This rising rates of inactivity and obesity are expected to lead to an osteoarthritis epidemic by the time the young folks today get old.

- Video - All About Arthritis

- Twisted Science: Pain Causes Arthritis

- 5 Painful Facts You Need to Know

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.