California Obliterates Record for Lowest Snowpack Ever

California's mountain snowpack will do little to slake the thirsty state this summer — only the tallest peaks are dusted with snow, and the most recent survey showed the driest snowpack in more than 100 years.

"We're not only setting a new low; we're completely obliterating the previous record," Dave Rizzardo, chief of the California Department of Water Resources' snow surveys section, said during a news conference today (April 1).

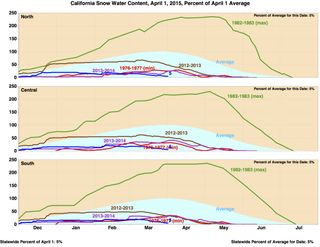

The Sierra Nevada snowpack typically supplies 30 percent of California's water. But this year, the snowpack's water content was just 5 percent of the average amount in the northern Sierra Nevada and 6 percent of the average in the central and southern Sierra Nevada during a snow survey by the water resources department on March 30. Today, at four key survey sites, they found no snow at all. [The 5 Worst Droughts in U.S. History]

The snowpack's previous record low, 25 percent of the average, was set during an earlier severe drought in 1977 and was repeated in 2014. The statewide snow records officially start in 1950, but in some areas, the records reach back to 1909, Rizzardo said.

With the snowpack essentially wiped out, Gov. Jerry Brown announced California's first-ever statewide mandatory water restrictions today. City officials must cut urban water use by 25 percent and require drip irrigation, while the state will encourage cities and homeowners to rip out their lawns, as well as make other cuts. [5 Ways We Waste Water]

California's abnormally warm winter and ongoing drought, which is now entering its fourth year, combined to drop the snow levels to record lows this year. When winter storms hit, precipitation fell as rain instead of snow because of the heat. And there were only two big storms that delivered much-needed rain: one in December and one in February. A persistent high-pressure ridge offshore has blocked these wintertime drought busters, called atmospheric rivers, from reaching California.

The one bright spot this year is that the two atmospheric rivers helped to fill crucial reservoirs in northern California, Rizzardo said. Both Shasta Lake and Lake Oroville are about half filled — well above levels seen during the 1976-1977 drought, he said. The reservoirs supply irrigation and drinking water for farmers and cities and help power hydroelectric dams.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We're lucky we benefited from these two big rainstorms. That's kind of saving us," Rizzardo said.

But the picture is bleak in areas farther south that were bypassed by the storms. The Exchequer Reservoir, east of Modesto, is at 9 percent capacity and could go dry this year, Rizzardo said.

Officials predict that the drought's effects will intensify in the coming months, with the end of winter rains and the advent of searing summer heat. "In some parts of the state, rural communities are in danger of running out of water or have already run out of water," said Heather Cooley, director of the water program at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California.

This year, drought will also have a severe impact on natural ecosystems, such as fish that need cold river runoff to spawn and trees that depend on snowmelt during the dry summer months. The demands could trickle up to humans, who depend on the same water.

For example, in an effort to preserve cold reservoir water for salmon, the East Bay Municipal Utilities District switched from taking bottom water to drawing top water from the Pardee Reservoir in late March. The utility was inundated with complaints from customers who hated the new taste and smell (warmer water has more algae) and had to switch back.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular